These alumnae are blazing trails.

She’s Worked Her Way Up the Ladder

Jeanine “Neen” Nicholson ’86 grew up across the street from a fire station in Pelham, N.Y. Both her father and grandfather were volunteer firefighters. But, as a girl, she never thought fighting fires was an option for herself.

Fast forward to 1991, Nicholson was living in San Francisco, “not feeling particularly fulfilled,” she says. While attending the gay pride parade, a friend handed her an interest card for the San Francisco Fire Department (SFFD).

“Women can do this?” Nicholson asked with excitement.

“If you can carry heavy things, you’ll be fine,” the friend responded.

Beyond the novelty factor, the thought of joining the fire department appealed to Nicholson’s desire to serve. “It feeds me,” she says.

Although it was 1994, women had been part of the department for only a few years. “There weren’t very many of us,” she notes, estimating that there were 50 women out of 1,500 firefighters. “We didn’t have separate bathrooms, and we didn’t have a separate changing room in most places.”

Today, as the recently appointed fire chief of San Francisco, Nicholson has her own personal bathroom.

This is how far she’s come:

For her first eight years with the SFFD, Nicholson was a firefighter with different companies around the city and then became certified as a firefighter paramedic, splitting her time between the fire engine and the ambulance. She was promoted to lieutenant in 2008, captain in 2012, and then to battalion chief in 2017.

Diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer in 2012, Nicholson had to undergo a double mastectomy and 16 rounds of chemotherapy. She was cleared to return to full duty 20 months later, but not before passing the physical agility test. Dressed in full gear, including a bulky air tank, Nicholson blasted through the course: swinging an ax, doing pull-ups, throwing a ladder, hauling a hose, and dragging a dummy.

At 49 years old, she broke the agility test record for the best time by a female firefighter: 8 minutes, 4 seconds. A coworker witnessing the feat commented, “That was like a 25-year-old dude doing it.” Nicholson remembers, “I was determined to get back to my job.”

At the end of 2017, the chief of the department selected her to be deputy chief of administration (the No. 3). As such, she oversaw training, homeland security, investigative services, human resources, and support services. “I got a really good view of what it’s like to run the department,” Nicholson says. Good thing, because she’d need it sooner than anticipated.

Out of 30 candidates, Nicholson was selected by Mayor London Breed to be the fire chief in May. “This woman has done something that I’m not certain has been replicated by any other member of the department,” Breed said during the swearing-in ceremony. “She [has] worked in every corner of the department all over the city and county of San Francisco… Working in so many capacities, from suppression to administration, she knows the fabric of this organization.”

Nicholson quickly established and outlined her priorities as fire chief. At the top of the list are homelessness and drug use, both of which are on the rise in San Francisco. Of all calls to the SFFD, 80% are medical, and 40% of those are persons with an unknown address. “There are a lot more behavioral-health and opioid issues than ever before,” Nicholson recently told the San Francisco Chronicle. “We definitely have a crisis on our hands.”

Disaster planning and preparedness are also significant. “It’s not if an earthquake is going to hit, it’s when,” Nicholson says. “We’re due.” At press time, officials were proposing $153.3 million for emergency water system improvements to reach all areas of the city.

Another priority is the budget, through which she’s requested a new health, wellness, and safety division for firefighters — who experience higher rates of cancer, PTSD, alcoholism, and suicide. She has already spearheaded educational and prevention initiatives, such as on-scene decontamination stations to remove toxic chemicals. “It used to be a badge of honor if you had soot on your face and your coat was filthy,” she recalls. “We would just walk back into the firehouse, take off our coats, and sit at the table to have a meal. So, we’ve had to institute some new practices.”

Being a public figure and a role model is part of the fire chief’s job. As San Francisco’s first openly gay fire chief, Nicholson takes that seriously. “I never had role models of any gay people when I was a kid. It was unheard of. So, I think it is really important for young people to have people with whom they can identify, so they can dream big.”

At this year’s San Francisco Gay Pride Festival, the SFFD participated, as it does in many of the city’s parades. As Nicholson marched past the crowds, she says, “It was really clear how proud people were of having the first LGBTQ chief. That was really touching to me.”

First job: “Working in the kitchen at a Cape Cod family seafood restaurant. I did everything: washed dishes; made pies, salads, coleslaw.”

Another first: In the mid-’70s, she wanted to sign up for Little League but was told “no girls allowed.” Nicholson’s dad went to bat for her, she got on the team, and she played third base “because I was the only one who could reach first base with a throw.”

On being a firefighter: “I have an affinity for bringing calm to chaos.”

At Colgate: Majored in sociology and anthropology; played ice hockey and rugby

Her cat: Among Nicholson’s several rescue animals is her gray feline friend, Humo, which means smoke in Spanish.

Advice for other women who want to be firefighters: “Don’t doubt yourself. Be prepared physically, psychologically, and mentally.”

She’s the brains behind life-changing research

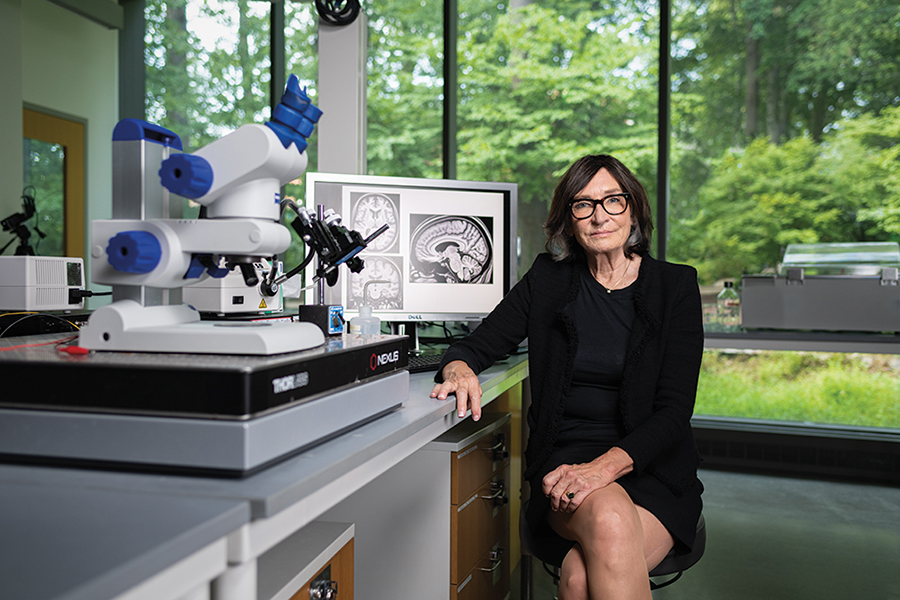

Michela Gallagher ’69 has found a treatment that may slow or even stop the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. As U.S. doctors diagnose a new case every 65 seconds, she’s racing against time.

Science, however, takes time, Gallagher emphasizes. She’s dedicated the last 20+ years to this research as a professor of psychological and brain sciences and neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University and its school of medicine. “I’m a scientist; I know how long it takes to get things done,” she says.

Gallagher didn’t set out to become a scientist. She was a fine arts major who transferred to Colgate from University College London for her senior year. Her fascination with visual art led to an exploration of the relationship between the visual system and the brain. “I was really interested in the fact that everything you see is going on in your brain,” she explains. So, after graduation, Gallagher pursued a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Vermont. “And then I got completely hooked on the memory system because it’s just amazing.”

She initially focused on episodic memory — how we remember daily experiences and the events of our life. Because a mild loss of episodic memory is a common condition as we get older, Gallagher began studying neurocognitive aging.

A surprising research finding in the early 2000s put into motion Gallagher’s pioneering work. She learned that the neurons that encode memories become overactive, not underactive, with aging. “You would think that the brain is slowing down,” she says. Instead, “we found that particular neurons located in the memory system were firing more highly.” The overactivity creates memory interference because “the overactive neurons failed to encode new information.”

At the same time, researchers began to identify mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as the transitional phase between normal aging and Alzheimer’s. In patients diagnosed with MCI, they found, there is even more pronounced overactivity in the memory system.

Gallagher began conducting studies with mice and identified a drug that reduced the overactivity. The drug, called AGB101, is an unusual antiepileptic prescribed as an adjunctive treatment with certain forms of epilepsy.

In 2008, Gallagher received a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to study the effects of AGB101 on humans. In the trials, participants with MCI took the drug at one-tenth the dose that doctors usually prescribe to people with epilepsy. “It was safe; there were no adverse effects,” she says.

Her team then used functional magnetic resonance imaging to scan study participants while they were performing memory tasks. While effectively reducing the hyperactivity, the medication also helped participants improve performance on memory tasks. “So it was a pretty compelling test of the hypothesis about the functional significance of overactivity,” Gallagher says. Since then, scientific evidence has shown that heightened neural activity drives the spread of Alzheimer pathology across connected neurons initially localized in the episodic memory system.

She conducted and published the research at Johns Hopkins. To develop the patents, licenses, and clinical trials, she founded the company AgeneBio. Gallagher is now running a phase 3 clinical trial with 830 patients in the United States, Europe, and Canada through AgeneBio.

In addition, she is running a substudy with 160 U.S. patients that’s looking at the protein called tau, which initially has a confined localization within the memory system but spreads over the protracted course of dementia. Tangles composed of tau can now be visualized by brain imaging methods, so the substudy can determine whether targeting neural overactivity limits the spread of tau. The NIH has given Gallagher a $20 million grant to visualize the location of tau in participants by using PET imaging.

The hope with these Alzheimer dementia prevention trials is that AGB101 proves to slow the progression of MCI. “If we can extend the amount of time it takes someone to get to the clinical stage of dementia by three years, the prevalence of patients with dementia decreases by 30 percent,” Gallagher explains.

She knows the toll dementia takes on patients and their families firsthand. Gallagher’s mother died of Alzheimer’s in 2003. “It’s tough on everybody. It’s totally emotional, personal, and a big stressor to undergo that process,” Gallagher says.

Her research has the potential to change lives. “If what we’re doing works, we could intervene earlier if you had the right biomarker to potentially prevent Alzheimer’s altogether,” she adds. “That’s a dream and the vision for the longer term.”

One of the first two women to receive a BA from Colgate

She is the first female graduate to earn a PhD, according to University records

Awards:

- The Melvin R. Goodes Prize for Alzheimer’s research

- The Mika Salpeter Lifetime Achievement Award by the Society for Neuroscience

First job: “I was an entrepreneur. I grew up riding horses, and my father said my sister and I could buy a horse if we paid for it. So we did everything in the world to raise enough money, like selling potholders and we ran a neighborhood newspaper. We were so committed, my father doubled our money and we got a horse.”

She’s Rebuilding Trust One Patient at a Time

African Americans are almost four times more likely to suffer from kidney failure than Caucasians. They also have a higher risk of the top two causes of kidney disease: diabetes and high blood pressure.

At the same time, they are less likely to seek care because of their mistrust of the medical community, explains Dr. Dinee Simpson ’00 of Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “That’s related to the dark history in our country where there’s been experimentation with African Americans — for example, the Tuskegee experiment,” she says.

As the first female African American transplant surgeon in the state of Illinois, Simpson is in a position to rebuild that broken trust and address this population’s health needs.

In addition to having a higher disease burden, African Americans’ lack of knowledge and access to care compound the problem, according to Simpson. “There are a lot of people who have kidney disease but never see a nephrologist or a kidney expert until they end up on dialysis,” she says. “This is a huge problem because when kidney disease is diagnosed early, it can be slowed.”

Implicit bias in the medical community is another issue. African Americans are less likely to be referred to a nephrologist, and many are not offered the option of transplant.

Simpson has looked at these disparities through the research side of her job, and her findings have supported the need for her brand-new Northwestern Medicine African American Transplant Access Program. The evolving program is designed to improve relationships with patients by setting up satellite clinics and sending medical professionals into the community for outreach.

“It’s a long process and not something we can do overnight,” Simpson says. “It will involve me and my group going into the community — rather than making them come to us — and having frank conversations, learning what their issues are, asking about their misgivings, and trying to address those.”

The multipronged program will also create interventions that focus on the top reasons why African Americans aren’t receiving transplants, such as obesity. Simpson’s team just received a grant to talk with one of Chicago’s South Side communities about ways to combat obesity.

Simpson’s own experience with a surgeon led her to this field. When she was a junior at Colgate, Simpson — who was a healthy student-athlete on the track team — learned at an annual physical that she had two breast masses that needed to be removed. “It was the first and only surgery I’ve ever had,” says Simpson, who underwent the procedure in Utica, N.Y., where she grew up. “There was something profound about being unsure of what was going on.” But after discussing the diagnosis and possibilities with the surgeon, Simpson was relieved to know that the surgery would result in a definitive answer. “That was really powerful to me,” she says. The chemistry major, who was planning to earn her PhD, changed courses and entered a medical track.

Her practical personality thrives on logical solutions. As a resident trainee learning about surgical subspecialties, something clicked for Simpson during her first living donor kidney transplant. “When we restored the blood flow, the [new] kidney turned pink and started making urine right away. There is no better instant gratification than that. Even after doing several hundred transplants, it never gets old.” Simpson also specializes in liver transplants.

Later that same day, she was working in the evaluation clinic where patients find out if they are transplant candidates. All six patients who visited the clinic that day were African American. “This was the first time I found out that kidney disease affected that population as profoundly as it does,” she says.

Simpson was shocked that she hadn’t learned this information previously in medical school. She also was surprised by the patients’ reactions to her. Although they were scared and skeptical of the circumstances, “just by me looking the way I looked, walking into their clinic room and introducing myself as part of the care team helped them tremendously,” she says. Simpson remembers the patients crying, hugging her, and telling her “how good it was to see me.”

The experience sent Simpson on a literature search, uncovering information about the disadvantages African Americans have when it comes to kidney transplants. “It felt like a place I needed to be, and I thought I could make a big difference for a huge population that is affected by this disease,” she says.

Now a year and a half into her role at Northwestern, it’s clear that she made the right choice.

First job: Sales clerk at Kids ’R Us in New Hartford, N.Y.

Recently received the SHEro Award from Distinctively Me, an organization that empowers adolescent girls.

Hardest parts of her job: 1. Being on the committee that decides who does and does not receive an organ transplant. 2. Balancing life as a surgeon, wife, and mother of two boys.

She’s the mayor

Nancy Baldwin ’78 is the first American to be elected mayor of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, U.K.

You’ve lived in Richmond since 1985. How did you become mayor?

I ran as a local councilor, and all the councilors elect the mayor. So they got together and elected me. I like a challenge.

In your career, you’ve held roles as banker, teacher, entrepreneur, and actor — is there a common thread?

Yes — communicating with people. And yes, I have done all those things. If I read it, I’d say, “she made that up,” but no. I’ve always needed an intellectual challenge.

I went to NYU for my MBA. I was chosen to study overseas at Manchester Business School (England), which is where I met my husband. I ended up becoming a vice president of corporate real estate in London. I enjoyed the customer contact, and there is a buzz to putting together a really good deal.

Then I made the ultimate career decision and became a mother.

When my son turned 2, things were on an even keel, so I asked myself, “What do I want to do?” I majored in German at Colgate and earned a master’s from University at Albany, SUNY. I love German, and there was a big demand for modern language teachers here in the U.K., so I became a teacher.

After my second son was born, I needed childcare, so I started a play group. Like a good little MBA, I took my clipboard to the busiest grocery in town to ask mothers with toddlers, “Would you like this kind of service? How much would you pay for it?” People said, “Please start something.” I still run that group today.

Next I got accepted to law school, but a friend asked, “What do you really want to do?” I replied that I’d always wanted to be an actress but never had the guts. So I thought, “Let’s give it a go.” I ended up going to drama school (with Tom Hardy). Nearly 20 years later, I’m still acting. Because of my business experience, I am asked to go into corporations to simulate challenging business situations in order to teach staff how to cope. That led to me getting an MSc in business psychology and starting a personal coaching business, mostly to help young women in their career choices.

Why did you first get involved in politics?

The Brexit vote to leave the European Union made me really angry for about a year, so my kids suggested that I run for local politics. I can’t change the world, but at least I can do something about the little stuff. As a student of German literature, this [philosophy] all comes from Goethe’s Faust: It’s the small things in life that make it worthwhile.

What has your position as a local councilor entailed?

Mostly, I am the residents’ advocate. However, I’m a liberal democrat, so I do a certain amount of party work, making people aware of our positions on various issues. The big issue is, of course, Brexit. The LibDems unapologetically think we should be remaining [in the EU].

How does your mayoral position differ from a U.S. mayor?

It’s a civic position and apolitical, so I represent all parties and all walks of life.

What does your weekly schedule typically look like?

I may start with breakfast with the Chamber of Commerce, talking about how to keep the High Street (Main Street in America) alive. I may go to a coffee morning at the almshouses [housing for the impoverished elderly]. Then I might visit a school and have afternoon tea at another project. We just had a week’s worth of festivities and talks celebrating the Thames, where I gave a prize to Sir David Attenborough.

Tell us about the two charities you selected for the mayoral appeal.

My charities include Home-Start, which supports and guides parents who are under stress (for various reasons, like mental health issues or unemployment) and have children under the age of 5. Children who come from an enriched environment do better in school, so this is all about early intervention. My other charity is the Otakar Kraus Music Trust, a local charity that provides music therapy to kids with additional needs. I wanted to do something with music because I’ve always played [she was a timpanist who played in the Colgate orchestra], and music can make all the difference.

First job: “A paper round subcontracted from my three older brothers when I was 10. I still say I was exploited.”

Term as mayor: 12 months, ending in May 2020

Mayoral garb: “I sometimes have to wear my tricorn hat, robe, and full regalia.”

The “chain of office” around her neck: “Every British mayor has a chain of office. Richmond’s particularly fine set of chains are from 1858. Every link represents a mayor from the past. They had to stop doing that in 1934 because it’s already two and half kilos of solid 18-karat gold. I have four different chains for different events. For example, I have a different chain for when I meet royalty because you don’t want to out-bling them.”

Stay tuned:

We see you, Class of 1974 alumnae, and next fall, we’ll be celebrating the anniversary of your arrival as the first co-educational class. Email magazine@colgate.edu to tell us about female trailblazers from ’74.

In the winter issue, we’ll be covering the 25th anniversary of Colgate’s Center for Women’s Studies, which is being celebrated in November.