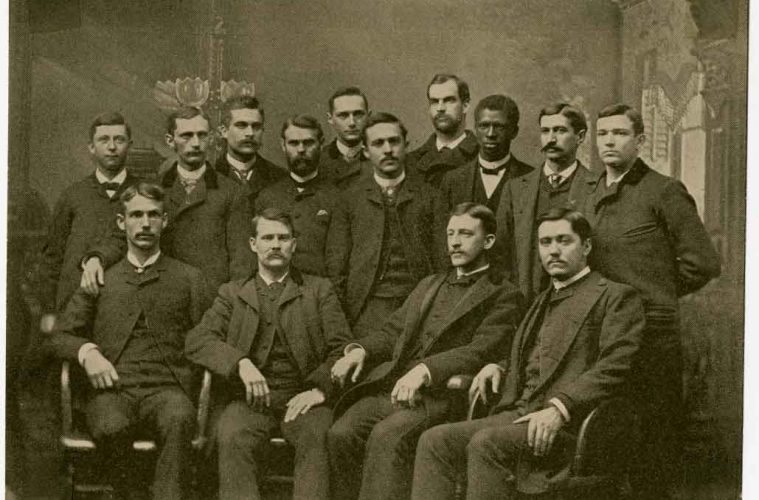

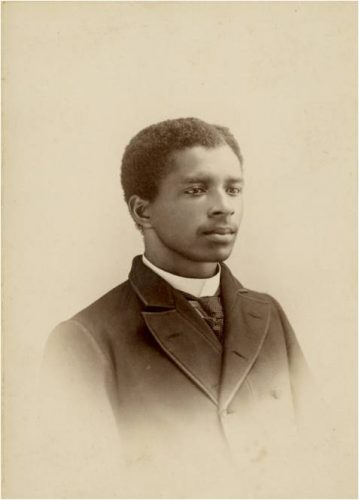

Above: The Class of 1887, including Matthew Gilbert, who became a minister, professor, and president of Selma University.

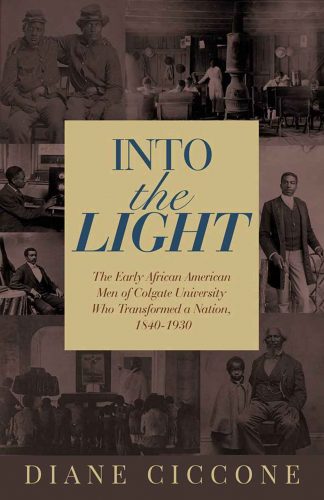

Jonas Holland Townsend was the first African American to attend this institution, in 1840. Henry Livingston Simpson was the first African American to graduate, in 1853. Five black college presidents came from Colgate. Diane Ciccone ’74, P’10 details revelations such as these — and the histories of pioneering black men — in her new book Into the Light: The Early African American Men of Colgate University Who Transformed a Nation, 1840–1930.

Jonas Holland Townsend was the first African American to attend this institution, in 1840. Henry Livingston Simpson was the first African American to graduate, in 1853. Five black college presidents came from Colgate. Diane Ciccone ’74, P’10 details revelations such as these — and the histories of pioneering black men — in her new book Into the Light: The Early African American Men of Colgate University Who Transformed a Nation, 1840–1930.

Ciccone herself is a Colgate pioneer — a member of the first graduating class of women, the first black woman on the Board of Trustees (1993–2000), and co-founder of the Alumni Of Color Organization. Colgate has recognized her with a Maroon Citation and the Wm. Brian Little Distinguished Service Award, and one of the Residential Commons is named for her.

Ciccone’s daughter, Kali MacMillan ’10, interviewed her for a Bicentennial Reunion event.

KM: What motivated you to tackle this topic?

DC: I chose African Americans because that is my heritage. Then I did a little survey and asked, who do you think was the first African American graduate? Most people knew about Adam Clayton Powell ’30. But nobody knew until Jason Petrulis [former Bicentennial research fellow] and Jim Smith ’70 [author of Becoming Colgate] started their research that the first African American to attend Colgate was in 1840, and the first graduate was in 1853.

[Image from Reunion talk]

Only two came came here before the end of the Civil War. They were born free. These men came seeking an education at a time when most black people were enslaved and were criminalized and brutalized for wanting to learn. That men who were enslaved until the Civil War came out of the South to get an education and went back to educate their people — I wanted to celebrate what they’d done.

I wanted to bring into the light these exceptional men and how they truly did help transform this nation. I wanted this to be celebratory, so Into the Light resonated that theme.

KM: Whom would you like to highlight?

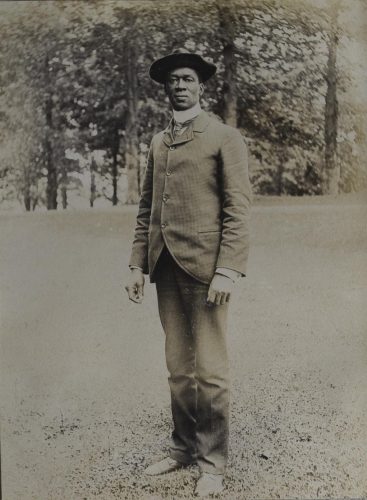

DC: The first African American Student was Jonas Holland Townsend, who was born outside of Philadelphia in 1820. He comes to Colgate in 1840, and he’s sponsored, but he’s gone in two years. We don’t know why he left, but afterwards, he was an abolitionist and activist. He goes to Albany, N.Y., which had a rich, engaged African American community, very involved in the antislavery movement and the Underground Railroad. He became a pastor there. He was one of the organizers for the first National Colored Convention in 1843; what’s significant is, that’s when the movement changed. Before then, the antislavery colonization societies were saying the slaves should be free, but they should go back to Africa. And then in 1843 there is a pivot to, “We helped build this country — we are going to stay here.” Townsend was one of the organizers. He was a confidante of Frederick Douglass. When Douglass went to England, he was the editor of the paper. From there, he was part of the Gold Rush, and started newspapers in California. His story is inspiring.

Samuel Howard Archer, Class of 1902

There’s Samuel Howard Archer, who graduated in 1902 and became the fifth president of Morehouse College. Talk about people who came through here who had influence! Martin Luther King Sr. was his pallbearer. Morehouse men were movers and shakers in this country. He patterned Morehouse’s colors after Colgate’s.

William Simmons stayed 1 year in 1868–69. He, his mother, and two siblings ran from slavery and ended up in Philadelphia. He learned how to read and write. He came to New Jersey to apprentice to be a dentist, but he didn’t want to be a dentist. So, he mustered in and fought in the Civil War. He was at the battle where General Lee surrendered. He came back, and a Baptist minister said he should go to Colgate. He didn’t really want to. In one of his letters, he said, “Not that I didn’t like the place, but I wanted to be somewhere that there was more than just me.” He graduated from Howard, and ended up becoming a college president in Kentucky. Then he wrote a book, Men of Mark, which at the time was like no other, chronicling the lives of various African American men, several of whom went to Colgate.

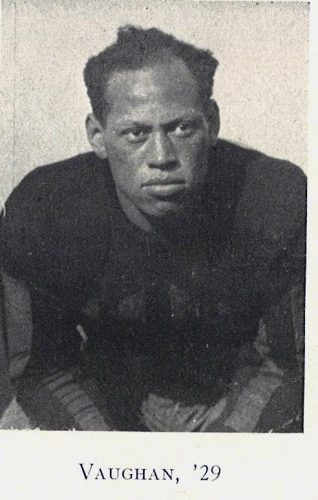

We had some dark moments here. I have a chapter called “Jim Crow Comes to Colgate.” Ray Vaughan ’29 was an outstanding football player; he was responsible for us beating Michigan and Syracuse. In 1926, Colgate was getting ready to play Navy, and depending on which version you read, Vaughan was benched, because, it was said, Navy wouldn’t play with a “Negro” (Navy publicly denied it). Vaughan was benched three times. I couldn’t make that link with President Cutten, but I do talk about him in the book. Going through yearbooks, after 1930, I did not see any African American men until the 1950s. It dawned on me that because of Cutten, there were no more blacks — he was a eugenicist. It was well known among alumni; I found letters. Adam Clayton Powell in 1946 or ’47 writes, “has the policy changed?” So we have this hole — in 1900, Colgate was ranked 8th in the number of African Americans graduates, and then after 1930, there were none. As for Vaughan, he went on to teach and coach football at Morehouse and supposedly played pro football with the Buffalo Bisons. He worked with the USO during the war years, taught, and was a family court probation officer in New York City.

KM: What was it like to read first-hand accounts?

DC: It was rare, to feel what somebody felt like back then. Sterling Gardner, Class of 1875, was enslaved until the Battle of Richmond. He came to Colgate at 16 years old. He wrote letters to his Baptist mentor in Virginia, saying, “I hate this place” and “I don’t have any money.” But, he said, “I’m not complaining.” He stayed because he knew that, if he succeeded, he would open doors for others.

Most of these men went back down South to become educators and ministers. Someone said to me, “Well, they didn’t have any other options.” But that really wasn’t true. Gordon Blaine Hancock (for whom one of Colgate’s Residential Commons is named) was a divinity student here and went on to Harvard. He was very clear that he could have gone anywhere because he had the education and credentials, but he was going back south. He taught at historically black schools because he knew that was his mission.

KM: Were there similarities in the lives of these black men and your time here?

DC: I came here in the fall of 1970. I didn’t know what to expect. That kind of isolation, but then the perseverance to make sure that you came here to do something and that you managed to get through, comes through with all those men and what they did in their lives.

KM: In shedding light on these men, what do you hope to inspire?

DC: At the sit-in in 2014, the students said, “We Are Colgate.” I am hoping that people will pick up the banner and tell their stories about what it was like to be here, who we are, and what we’ve been, so that future generations can take pride in this place.

From Chapter V: Freedom, Reconstruction, and a New Hope

“W.E.B. Du Bois did a study to determine which colleges Blacks attended prior to 1900. Du Bois’ study notes nine Colgate graduates, which tied Colgate at #8 among predominately White Colleges on Du Bois’ list…These men became part of the Black educated elite. They left their familiar surroundings and family to attend Colgate during a time when the Freedmen’s Bureau, a group of northern Whites and Blacks, was organized to support Black schools and colleges in the South. These men understood and took on the challenge, of using their education and status to work toward educating the minds and souls of fellow Black men and women, who had only recently been released from their physical bondage.” — Into the Light, pg. 54–55

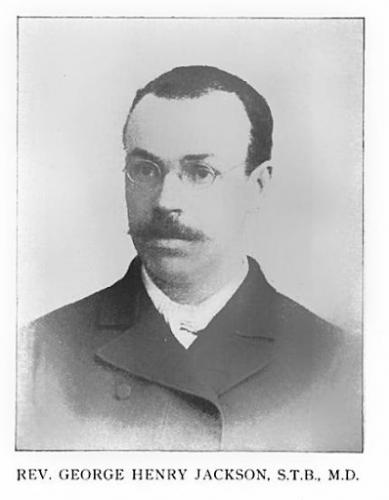

Rev. George Henry Jackson, Class of 1887

Matthew Gilbert, Class of 1887

Tidbits

- Into the Light is available at the Colgate Bookstore.

- The documentary Path of Duty, researched by Ciccone and former Bicentennial fellow Jason Petrulis, tells the story of three African American alumni.

- Ciccone is interviewing alumni of color about their experiences at Colgate and beyond “so that 50 years from now others won’t struggle like Jim Smith ’70 and I struggled to find out what it was like to live here.” To participate in her oral history project, reach her at bookciccone@gmail.com.

- Imani Ballard ’18 and Max Longoria ’21 assisted Ciccone in researching the book.