If there is such a thing as a time of truest innocence in a person’s life, this was it for me. I was 10 years old, on a family summer exploration of England. We’d traveled from our home in India to France, and then crossed over to England in our luridly yellow Volkswagen camper van, exchanging the faces of Saint-Exupéry, Cézanne, and Eiffel on French francs for the visage of Queen Elizabeth II on every British note and coin. I remember feeling a sharp loss at the exchange; the sum of my weekly allowance, carefully hoarded in Indian rupees over the last year and calculated into French francs just weeks ago, was suddenly divided by 10. The turmoil of what to spend it on was settled within minutes of entering a London bookstore. My questing fingers settled on treasure finer than any: a boxed set of Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Prydain. Did Galahad feel this glorious and exalted when he held the Holy Grail in his hands? Perhaps.

What is arguably Alexander’s masterwork could not have come to me by chance. Its plot is, very simply, the coming of age of Taran from assistant pig-keeper to the High King of Prydain. At a deeper level, it is, among other things, a parable about innocence. What Taran taught me through his valiant attempts at heroism, romance, magic, and wisdom, was that innocence need not be sacrificed for maturity. That would come to mean a lot to me, then being on the cusp of middle school, that inexhaustible hive of sociopolitical maneuvering. Less facetiously, that still means as much today, if not more, 30 years later as a writer of fantasy adventure for children.

At that time, it was probably the most money I had ever spent on anything. As we drove from London to Stratford-upon-Avon, York, and eventually into the Lake District, I traveled also with Taran throughout Prydain, to ruined Caer Colur, and to deadly Annuvin. Not once did I regret my first major transaction. Although I had read some fantasy work before, it was with Prydain that I began to dream stories. All summer long, I stole away into lush English woods and fought malevolent bushes with scavenged sticks. When I emerged from Prydain and Britain at the end of my family’s vacation, I came out wanting to be a writer. It seemed as evident and natural as breathing. Alexander had, through his story, infected me with the blessed affliction of loving the written word.

How did Taran keep his innocence intact? I think he simply clung on to the certainty that the world was good. And maybe that’s what innocence is. Not the facile notion that innocence is perforce lost with experience. But that if all your experiences only reinforce your belief that the world is corrupt, and there is no way to live in it unless you become corrupt yourself, then innocence is lost. If that’s the case, then Alexander did more than just grace my summer — he saved my life.

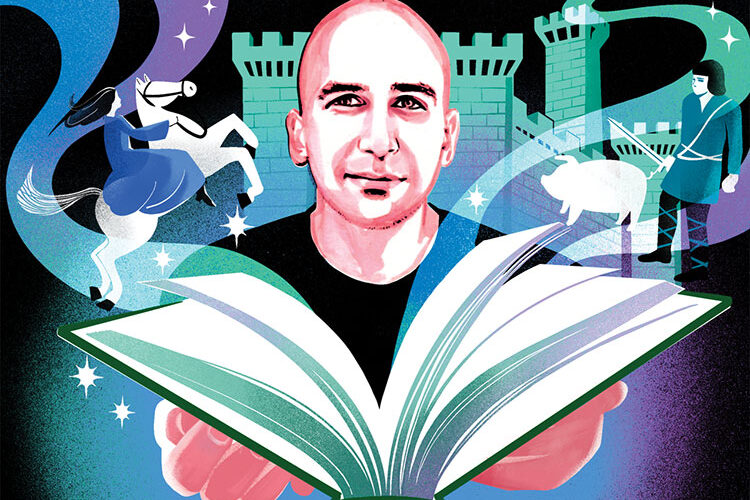

— Olivier Lafont ’01 is the author of the children’s book Oop and Lila: Lost in the Scarabean Sea (Hachette, 2020). At Colgate, he was an English and theater double major and participated in the London English Study Group. He lives in Paris, where he also works as an actor and screenplay writer.