Photography by Mark DiOrio

Historical images courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives

Visualize yourself sitting in a Colgate classroom.

As you unpack your notebooks and begin listening to your professor lecture on the Challenges of Modernity, you look outside the window, onto the academic quad. You know the storied history of West Hall, built by the hands of Colgate students before you. But what about the other structures that make up the campus? After class, you’ll head to your next course in Hascall Hall, but who was Hascall?

We’ll tell you.

Hascall Hall

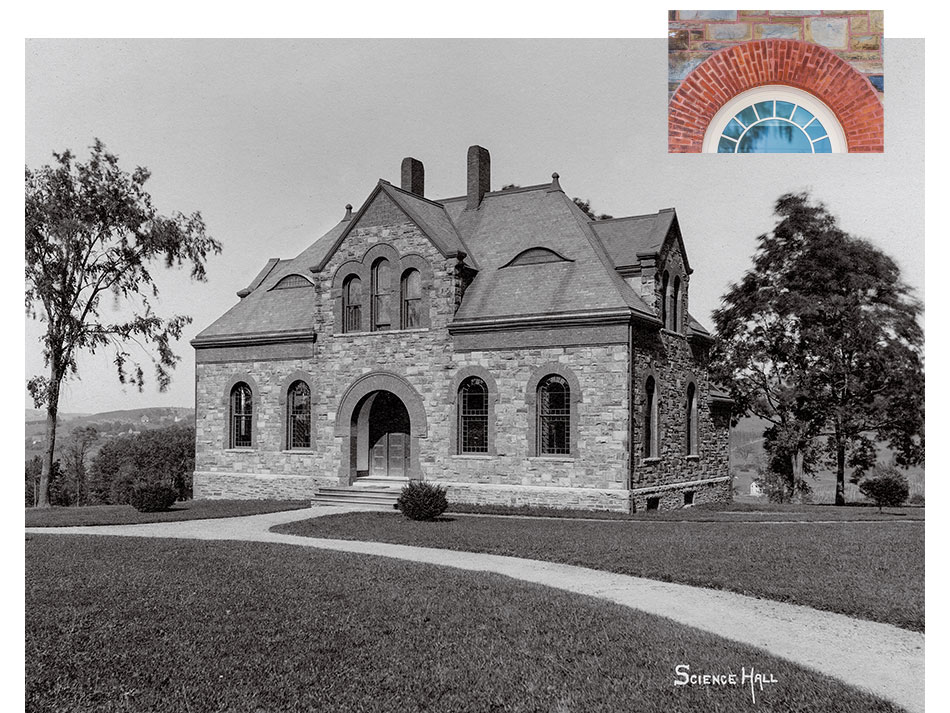

Hascall Hall has had several iterations since its opening in February 1885: It was first called the “Chemistry Laboratory” and later “Old Biology.” The building, designed in the Queen Anne style, demonstrated President Ebenezer Dodge’s will to expand the sciences at what was then Madison University. Dodge combined his finances with Samuel Colgate’s and other donors’ — the structure, made of local stone and trimmed with red brick, would cost $10,000.

The building would become one of the first on campus dedicated exclusively to classrooms. On the first floor, students studied chemistry and physics, and on the second floor, they conducted quantitative analyses — taught by Joseph F. McGregory.

To thank Dodge for his contribution to the study of science, the University erected a stained glass window with his likeness over the building’s west entrance. The window, removed in 1971, was gifted by the Class of 1886, the first to use the building. In 1906, when the University matched a donation from Andrew Carnegie, an extension was added to the east side of the building.

“The decline of ‘Old Bio’ was in part because the University had planned on its destruction from the late 1920s — and certainly the 1930s — as a way of clearing the quad and view east from the Chapel,” says Professor of Art and Art History Robert McVaugh, who specializes in 20th-century architecture. In the early 1970s, the building nearly met its maker — it was in grave disrepair, and the University planned to demolish it in favor of the new Olin Hall. Wanting to “Save Old Bio,” students and faculty members fought this idea, and Hascall was eventually added to the National Register of Historic Places. This gave the opportunity to make use of federal funds to resuscitate the building.

One of the most recent renovations of the building came in 1976, by architecture firm Rogers, Butler, and Burgun — they also built the original Olin and Wynn halls. The Carnegie expansion was removed, and the building was restored and renamed to honor one of Colgate’s 13 founders.

Namesake: Daniel Hascall was the seminary’s first teacher and the author of the oldest-known publication by a faculty member: a treatise on the meaning of baptism from 1818. Hascall was one of only a few college-educated Baptist ministers in New York at the time of the seminary’s founding, and he was a proponent of “a more literate and better educated clergy,” according to James Allen Smith ’70 in Becoming Colgate. It’s clear Hascall is a lasting figure on campus — he designed and built West Hall, and together with Professor Philetus B. Spear, he played a large part in keeping the University in Hamilton during removalist efforts in the mid-1800s.

Do you know what geological feature is in the walls of Hascall Hall? Check the bottom of this article for the answer.

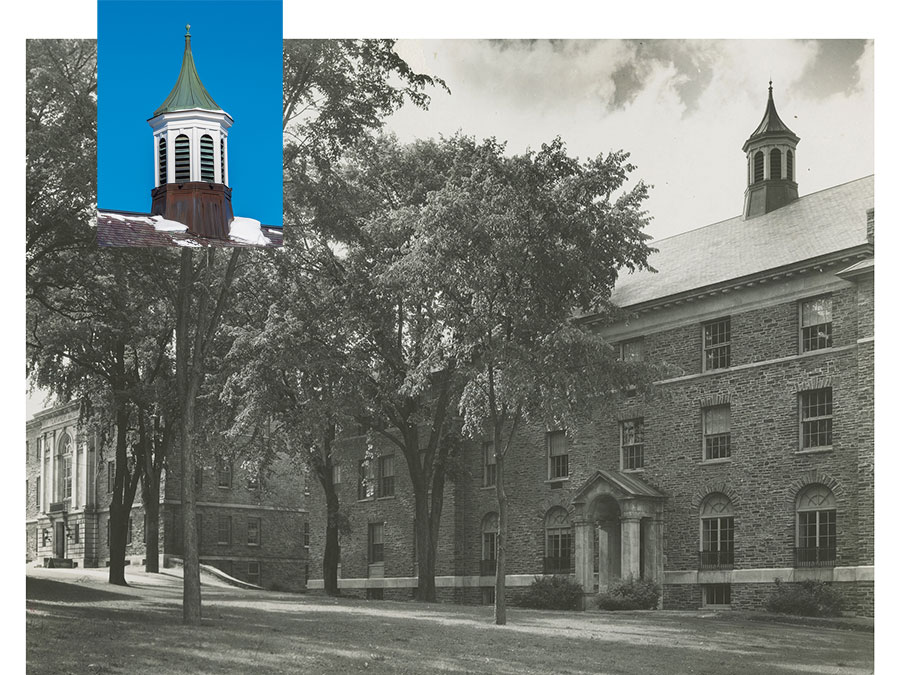

McGregory Hall

True to its namesake, who revolutionized the sciences at the University, McGregory Hall (dedicated in the early 1930s) was built to house the Department of Chemistry.

In fact, McGregory assisted the architect, Walter B. Chambers, in planning the building to suit its future chemistry students. The building was the bequest of Evelyn Colgate and was also a gift of her father, James C. Colgate, Class of 1884. It underwent renovations in 1981.

Namesake: The charismatic Joseph F. McGregory was hired by President Dodge in 1883 at a time when science was a fledgling subject at the University. During his time at Madison, McGregory completely changed the way the University approached the sciences, “and over a forty-six-year career, his magnetic personality and brilliant teaching drew many more students into the sciences,” according to Smith in Becoming Colgate. He was also active in the Hamilton community, conducting the choir at the First Baptist Church, and he may have organized the University’s first chorus.

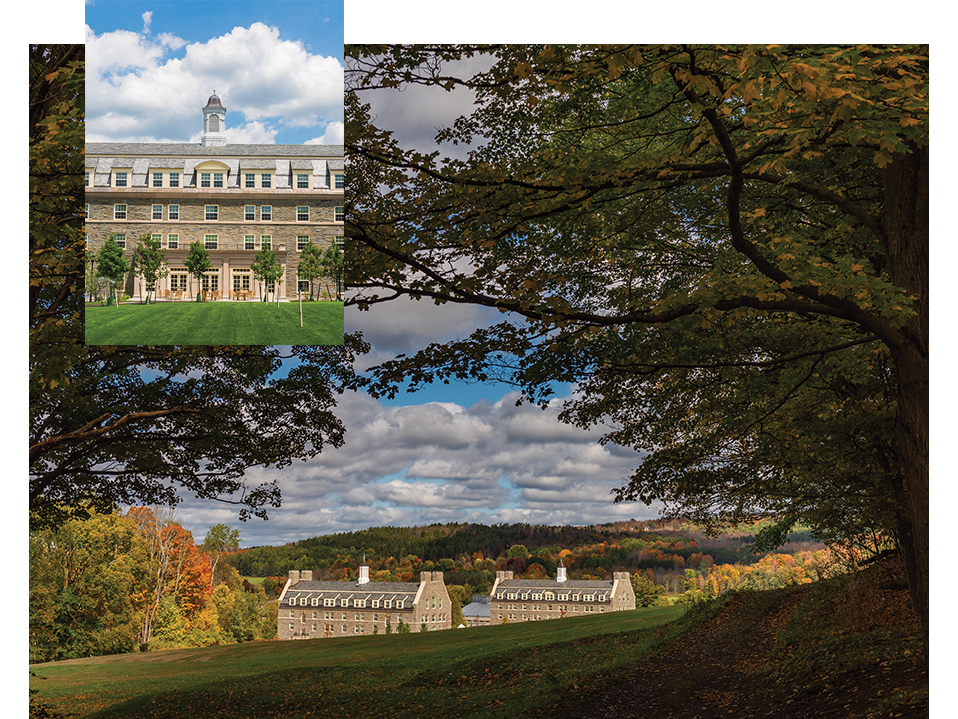

Burke and Pinchin halls

Dedicated on the eve of Colgate’s third century, Burke and Pinchin halls stand as a testament to the University’s proud traditions and bold ambitions.

These two new residence halls are the first to be added to the upper campus since Stillman Hall in 1927. Designed by Robert A.M. Stern Architects to blend into the campus architecture, the buildings adhere to LEED Silver sustainability standards. The halls celebrate the living-learning model, containing seminar rooms and social lounges, in addition to each having 100 beds for students. Pinchin Hall was funded by an anonymous couple, and Burke Hall was named in recognition of a $10 million gift from Gretchen Hoadley ’81 and Steve Burke ’80, P’11,’20.

Namesakes: A member of the Board of Trustees, Gretchen Hoadley ’81 Burke P’11,’20 majored in English and earned her MBA at Harvard. Steve Burke ’80, P’11,’20 earned his degree in history. Their name on the building across the courtyard from Pinchin Hall is fitting: “During my student days, [Jane Pinchin] was a favorite faculty member and my thesis adviser,” Gretchen says. “When Steve was a trustee, we knew her as an active interim president.”

Jane Lagoudis Pinchin, Thomas A. Bartlett Chair and professor of English emerita, first came to Colgate in 1965 to teach Core 17, a literature course. She was one of the first two women to teach full-time at the University. Pinchin taught part-time from 1969–70 and then entered a tenure-stream position. She served as provost and dean of the faculty during her career at Colgate, in addition to interim president from 2001–02.

Dana Arts Center

Love it or hate it, Dana Arts Center is difficult to miss. The brutalist, concrete building was funded in part by the Charles A. Dana Foundation.

In 1962, the foundation’s namesake visited campus and, after seeing the need for new arts facilities, offered $400,000 if the University raised another $800,000. Designed by Paul Rudolph, the building plans originally featured a bridge connecting it to the quad. “Why have that bridge?” Dana questioned, according to the April 10, 1964, edition of the New York Times. “Walking is good exercise for the students.”

The plans also incorporated a concert hall, art gallery, and rehearsal spaces, which were all nixed when the project became too costly.

Many structural elements of Dana are puzzling for a space built for the arts. For example, concrete walls do not support the melodies played by music majors, and rehearsal and teaching spaces are cramped. Unfortunately, the building hasn’t changed much in the past 50 years: “Dana’s deficiencies have not been remedied,” Smith notes in Becoming Colgate. However, upon Dana’s completion, students were excited to have a place devoted to the arts and creativity. According to the Feb. 29, 1968, Maroon, to “focus appreciative attention on the new Dana Arts Center,” students planned a 14-day festival called Fortnight, which ended with a performance by The Doors.

Even though the version of Dana that exists today is a far cry from what was originally planned and needed, it’s a place for the arts to call home. Architecture students and fans of brutalism commonly visit the building, the first to use Rudolph’s split rib block concept. And, if you’ve ever been inside Dana, you know that the building gives off a certain feeling. Professor of Music Bill Skelton said it best in the March 1989 edition of the Scene: “The light changes the building every day. At night, it scares you to death sometimes, and in the morning it sings.”

Namesake: Charles A. Dana was a legislator, industrialist, and philanthropist who started his foundation in 1950. The foundation supported building projects at several other higher education institutions before Dana Arts Center was constructed.

Harry H. Lang Cross Country Course and Fitness Trails

For a quarter century, students have witnessed the beauty of the Chenango Valley from these trails. Dedicated on June 2, 1996, the space was funded by Harry Lang Jr. ’48, alumni, parents, friends, and several leadership donors. Colgate’s cross country teams compete on the course, and there are 5K and 8K trails in addition to mountain bike paths. Some other notable aspects: the Darwin Thinking Path, the Double Loop Trail, and, of course, the Ski Hill (we all have of a memory of that one). At the end of the Edge Trails, you’ll stumble upon Colgate’s quarry, which lent its stones to several campus buildings.

While you’re on the trails, take a look at some wildlife: “Colgate’s forested lands provide a mini-sanctuary for some of the most colorful and charismatic songbirds in North America,” Director of Sustainability John Pumilio says. “With a careful eye, strikingly beautiful birds such as the scarlet tanager and indigo bunting can be seen along the Harry Lang trails. Each spring and summer, these trails come alive with a beautiful chorus of bird songs. Thrushes, wrens, and warblers are among the species singing above springtime walkers, hikers, and outdoor enthusiasts. Songsters, such as the beloved wood thrush whose population has declined by 62% since the mid-1960s, breed and depend on Colgate’s forest to help ensure the next generation of thrushes.”

Namesake: Born in Buffalo, N.Y., Harry Lang Jr. ’48 devoted his life to service. After high school, he joined the Army and was stationed in Germany during WWII. He came to the Hill to study history and spent his time outside of class competing in lacrosse and enjoying the company of his brothers as a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon.

Upon earning his master’s degree from the University at Buffalo School of Social Work in 1952, he embarked on a 42-year career at Hillside Children’s Center in Rochester, N.Y. “Frequently working 12–14-hour days, he lived on campus for many years, often eating meals in the cottages with the children and staff,” read his obituary in The Buffalo News. “He was committed to ensuring that Hillside provided high quality services that were in the best interest of children and families.” In his free time, Lang watched his beloved Buffalo Bills at every home game for more than 30 years.

Lang died on Dec. 16, 2020, at age 93.

Spear House

Unlike many of the other buildings on campus, Spear House was originally a faculty residence, first to Professor Joel Bacon in 1835 and then Professor Philetus B. Spear, who bought the property then named “Claremont” in 1838. The stone house was “situated so as to command sweeping vistas through the woods toward the west and the village and the valley to the north,” says Howard D. Williams in A History of Colgate University: 1819–1969. After Spear’s use, the building was briefly occupied by a fraternity, followed by various faculty members. It was renovated in 1935 to house the Samuel Colgate Baptist Historical Collection, but was renovated again in 1947 and has since held University offices.

When Spear resided in the house, he also owned the land around it. This became an issue when the University planned to build James B. Colgate Hall, delaying the project for about a decade. “Colgate’s frustrated aspiration for a library on the site had significant ripple effects we still feel in the organization of the campus,” says McVaugh.

Namesake: Philetus B. Spear devoted most of his life to what would later become Colgate, graduating from the college in 1836 and then from the seminary in 1838. He taught Hebrew and Latin for 60 years, in addition to acting as treasurer of the University.

Bolton House

Less than a mile from the Hill sits 84 Broad Street, also known as Bolton House. Built in 1927 and previously housing the Sigma Nu fraternity, it transitioned into a women’s residence and resource center in 1977. “One of the misunderstandings about the house is that it is a sorority — it isn’t … the house is open to everyone on campus, not just a select few,” writes Jean Walsh ’80 in the Sept. 17, 1976, issue of the Maroon. From 1985–94, Bolton was the women’s studies theme house. Now, it actually is a sorority house: Members of Delta Delta Delta occupy the residence.

Namesake: Frances P. Bolton H’40, Elisha Payne’s great-granddaughter, was a Republican congresswoman from Ohio who advocated for education, health care, and civil rights. Bolton took her late husband’s senate seat in 1940, becoming the first woman elected to the position from Ohio. As a woman in office during wartime (and as a survivor of the 1918 flu pandemic), she wrote the Bolton Act, which created the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps to help with health care during WWII. The Bolton Act did not discriminate based on race or ethnicity: “What we see is that America cannot be less than herself once she awakens to the realization that freedom does not mean license and that license can be the keeping of others from sharing that freedom,” Bolton said, according to congressional records.

Campuses are places of the imagination as much as they are physical arrangements of buildings and lawns. … Over the years, different ideas of what Colgate ought to be came to the fore, and the campus reflected these new notions. So now we come to the Colgate campus with its history written in stone. But we also come to a place where aspirations and dreams … conjured up buildings and spaces designed to reflect or inspire our highest ideals.

— President Brian W. Casey, in the foreword to the leaflet for The Hill Envisioned, a Bicentennial exhibition, Clifford Gallery, April 25–June 3, and Aug. 27–Oct. 3, 2018.

Read about the University’s building future in the next issue of Colgate Magazine.

Do you know what geological feature is in the walls of Hascall Hall?

Answer: Look closely at the front and left sides of Hascall Hall, and you’ll find fossils imbedded in the stones that make up the building’s exterior.