The way the story was shared in the news a couple of years back, you’d think Charles Tillman, known as one of the best cornerbacks in Chicago Bears history, was the first retired professional football player to become an FBI agent. But you’d be wrong. That honor actually belongs to another (albeit briefly) former Bear — 86-year-old Milton Graham ’56.

As a senior in high school in Defreetsville, N.Y., Graham was a hoops star — so much so that Colgate recruited him to join the basketball team. That wasn’t enough for Graham; he decided to give football a try as well.

“I decided to try out at Colgate because I was 6’6″ and 270 pounds — big and active. The varsity coach saw me after one practice and called me in. He said, ‘Son, we’re going to make a football player out of you.’ And they did.”

Graham went on to earn AP All-East Honors in 1954 and the United Press International honorable mention All-America honors in his senior year. He didn’t give up on basketball either and captained Colgate’s team his senior year. Thus, upon graduation in 1956, Graham had a choice many a man would envy: play pro football for the Bears, which drafted him, or play basketball with the Syracuse Nationals (today’s Philadelphia 76ers) in the NBA, which also drafted him.

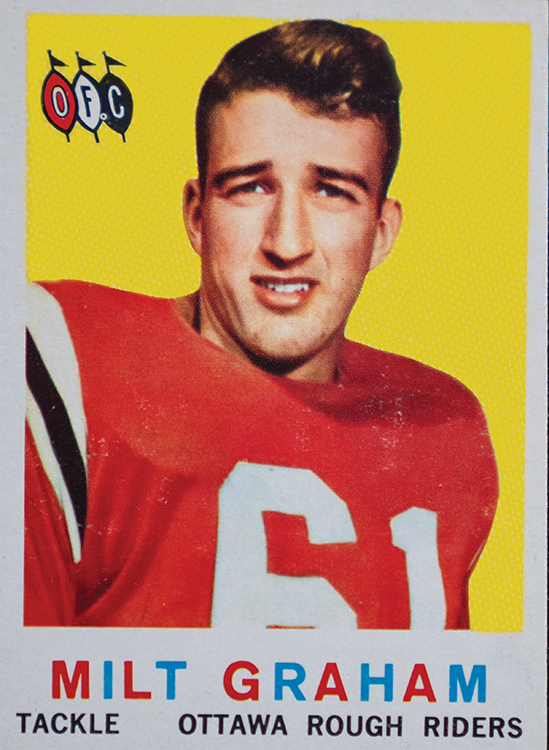

Football won out, but Graham never played a game with the Bears and soon joined the Canadian Football League’s (CFL) Ottawa Rough Riders. There he was part of the CFL All-Star team in 1958 and a member of the 1960 Grey Cup (CFL championship) winning team. “I had three or four touchdowns playing tackle,” he recalls. “That doesn’t happen often — then or now.”

In 1961 he joined the American Football League’s Boston Patriots (which later became the New England Patriots), and he was the Unsung Hero of the ’62 squad.

After two years with the Boston Patriots, Graham decided to retire in 1962 because of the physical toll on his body. While concussions are the talk of the NFL these days, in the early 1960s it was just part of the game. “They referred to it as ‘getting knocked out,’” remembers Graham. “A coach would come out onto the field and ask if you knew how many fingers he was holding up and if you knew where you were. I was knocked out two times but went back into the game both times.” Graham also has a metal plate in his neck from a football-related injury: “My neck took a beating,” he says.

An acquaintanceship with an FBI agent pulled Graham to the bureau, where he would remain for 20 years. In the 1960s he was sent down south to enforce the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He often dealt with the Ku Klux Klan: “Every day was a struggle with those lunkhead Klansmen and their sympathizers,” says Graham. He proudly recalls being part of an FBI team that brought to justice the white murderer of an African American man — one of the first successful prosecutions, according to Graham.

His work with the FBI — first in the South and later in New York City working to capture fugitives — earned him notice from top brass, including FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. “I was involved in 8 to 10 cases that came to Hoover’s attention,” says Graham, who has the letters of commendation to prove it. “What the FBI did meant a lot to me. It changed the country.”

As an agent, Graham recalls only one standoff in which he had to shoot his weapon in defense. While not a fan of firearms, Graham proved to be an excellent shot and served as a firearms instructor at the FBI. “It’s a paradox in a sense,” mused Graham. “I was a firearms instructor, but I never liked it. If I had to use my gun, I wanted to come out on top.”

Life has certainly held adventure and excitement for Graham. He has scrapbooks chronicling his football playing and FBI career that he shares fondly with a ready smile. And he has his memories.

— Excerpted from an article by Vira Mamchur Schwartz published in the Daily Voice