Honoring Colgate’s longest-serving professor, Jerome “Jerry” Balmuth

May 8, 1924–Sept. 28, 2017

A disciple of debate and a lover of language, Professor Jerry Balmuth was a masterful rhetorician. Through his words, he articulated his philosophy of how one should live; even more importantly, he embodied those qualities.

A disciple of debate and a lover of language, Professor Jerry Balmuth was a masterful rhetorician. Through his words, he articulated his philosophy of how one should live; even more importantly, he embodied those qualities.

Balmuth, the Harry Emerson Fosdick Professor of philosophy and religion emeritus, came to Colgate in 1954. He joined a department with “unusually strong teachers” — luminaries including Huntington Terrell, Stephen Hartshorne, and Herman Brautigam — and “a strong following among students,” Balmuth recalled in a 2004 Scene article. Alongside these scholars, he established himself as a rigorous professor who yearned to spark a fire in his students.

“I believe education is not a demonstration of the knowledge of the instructor but rather an attempt to provoke the students into discovery of his or her own talents,” he said in a 2008 video interview. “If we give them the challenges that come with intellectual imagination and reflection upon learning itself, they will respond and they will discover for themselves that learning is the one pastime that continues to pay and repay in its richness and its range of significance.”

While he strove to support students’ autonomy, Balmuth also noted: “Liberal education is moral education. Meaning, ultimately, there is a large section of liberal education that is purely designed for the understanding, but all that understanding goes into living a life in a certain way. And moral education is the choices of one’s actions in day-to-day life and ultimately in the choice of not only how to live one’s life but also how to relate to others in that life.”

Known for being welcoming and amicable, Balmuth was an early proponent of inclusivity. When he joined Colgate, he was one of only two Jewish faculty members in the department. Overall, the university community lacked diversity — something students and professors, including Balmuth, would seek to change in subsequent years.

He was a mentor to many African-American students and taught in a nascent version of the Office of Undergraduate Studies. Outside the classroom, Balmuth was one of a few professors who, in the 1960s, joined students in a peaceful sit-in during the civil rights movement.

“The unexamined life is not worth living.”

He was supportive of Jewish life at Colgate as well and helped spearhead the creation of the Saperstein Jewish Center on campus. In the village of Hamilton, Balmuth and his first wife, Ruth, were also instrumental in the founding of an interfaith Sunday school.

As Balmuth was known to quote Socrates and would often say, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” In recognition of this, some of Balmuth’s former students and colleagues reflect here on how he led his life with thoughtfulness, wit, and wisdom.

Undoubtedly, there are more who remember Colgate’s longest-serving professor — a man who taught more than 9,000 students in his 56 years at the university. Share your recollections of Balmuth in the comments section below.

— Aleta Mayne

In memoriam

Jerome Balmuth’s storied career at Colgate began in 1954, when he joined the Department of Philosophy and Religion after receiving his undergraduate degree from Amherst College and a master’s in philosophy from Cornell University. In 1995 he was named Harry Emerson Fosdick Professor of philosophy and religion. He retired in 2010, after 56 years of full-time teaching; his love of teaching brought him back to the classroom for part-time teaching for another year.

Jerome Balmuth’s storied career at Colgate began in 1954, when he joined the Department of Philosophy and Religion after receiving his undergraduate degree from Amherst College and a master’s in philosophy from Cornell University. In 1995 he was named Harry Emerson Fosdick Professor of philosophy and religion. He retired in 2010, after 56 years of full-time teaching; his love of teaching brought him back to the classroom for part-time teaching for another year.

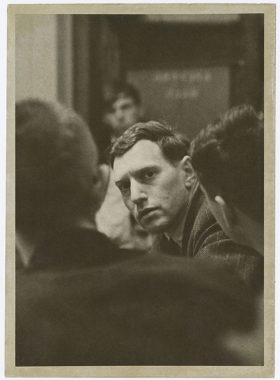

Balmuth was born in Brooklyn on May 8, 1924. He was drafted into the Army in 1943 and served in the European theater during the final Allied assault on Germany; he was assigned to the Dachau concentration camp shortly after it was liberated and turned into a POW camp. He attended officer school, was commissioned as a second lieutenant, and was discharged at the rank of acting captain.

The GI Bill enabled Balmuth to study at Amherst. There he found his calling in the study of philosophy. At Cornell, he studied with many of the leading lights of 20th-century philosophy, and through them first encountered the thoughts of Ludwig Wittgenstein. This encounter set Balmuth’s path for his research and teaching.

A point of pride to Balmuth was how many of his students went on to graduate study and successful careers as teachers of philosophy; to the end of his life, he kept a mental tally of all 100-plus such former students. Balmuth garnered every teaching award that Colgate offers: the Alumni Corporation Teaching Award (1988), the AAUP Professor of the Year (1992), Phi Eta Sigma Professor of the Year (1994), and the Sidney J. and Florence Felten French Prize for outstanding teaching (1997).

He was predeceased by his first wife, Ruth, and his brother, Daniel. He is survived by his wife, Martha; his sisters, Lorraine Widman and Marilyn Stolove; his children, Deborah Balmuth (Colin Harrington), Beth Raffeld (Philip Khoury), and Andrew Balmuth ’89 (Akemi Ohira Balmuth); and his grandchildren, Eli Raffeld ’10 (Jennifer Wu Raffeld), Miriam Raffeld, and Hanna Balmuth. He is also survived by many nieces and nephews, including David Balmuth ’82; and grandnephews and grandnieces, including Amy Balmuth ’17.

Gifts in memoriam may be directed to The Jerome Balmuth Endowed Scholarship Fund, through the advancement office of Colgate University.

Contemporaries

“When I came here in ’63, Jerry was a young faculty member getting established,” remembers Tony Aveni, Russell Colgate Distinguished University Professor of astronomy and anthropology and Native American studies emeritus. “He was friendly and open; and he loved to argue, but that’s what a logician does for business.” Balmuth showed that arguments aren’t necessarily a negative activity, Aveni explains. “A good philosopher knows that reason and argumentation make up the dialogue in so many parts of the academy,” Aveni says. And Balmuth was always a “good guy to exercise your brain with.”

If Balmuth had one bad habit, Aveni notes, he was often tardy for functions — especially lectures — but Balmuth made up for it with a knack for always asking penetrating questions at the end. “I admired him for that; I even envied him that he could do that,” Aveni says. “He had a sharp mind.”

Another cause for his admiration of Balmuth, Aveni adds, was his collegiality during the revision of Colgate’s core program in the early ’80s. As director of university studies who led the modifications to the core curriculum, Aveni faced some resistance from other faculty members who didn’t want changes to the philosophy and religion program. “But not Jerry,” Aveni says. “I was quite impressed with how secure Jerry was with his idea of what belongs in the academy. He was very persuasive and ended up being one of our staunchest allies in altering the program.”

“I was quite impressed with how secure Jerry was with his idea of what belongs in the academy.”

— Tony Aveni, Russell Colgate Distinguished University Professor of astronomy and anthropology and Native American studies emeritus

A guiding light

Alonzo McCollum ’72, MA’73 recalls that coming to Colgate from Newark, N.J., in the late ’60s “was a big change of scenery, but Professor Balmuth made it more comfortable.” Balmuth was McCollum’s adviser during all four years of the philosophy and religion major’s undergraduate studies. McCollum remembers having dinner with Balmuth and his family at the professor’s house on multiple occasions. “We talked about philosophy and religion, and the civil rights movement,” McCollum says.

The alumnus adds that he recalls the professor often speaking about the connections between the struggle of African Americans, women, Native Americans, Latinos, and other disenfranchised groups. “He was an important example of what America should be about: openness, respect, honor, integrity, and diversity,” McCollum emphasizes. Noting that Balmuth was outspoken about Colgate’s need to be more inclusive, McCollum adds, “Professor Balmuth walked the walk and talked the talk.”

Due to Balmuth’s and other Colgate professors’ encouragement, McCollum says, he was motivated to “stick to it and be serious about my scholarship.” After receiving his bachelor’s degree, McCollum earned his master’s in student personnel administration, guidance, and counseling at Colgate. Balmuth’s influence, McCollum says, was integral in shaping his career path. Today he is the director of the Educational Opportunity Program at SUNY Old Westbury. McCollum wanted to work in a field that helps disadvantaged youth who face barriers because he himself came from a similar background. “I specialize in helping students get in school, stay in school, graduate, and become productive citizens,” he says. “I connect that to my experience at Colgate.”

McCollum maintained his connection with Balmuth and the university over the years, returning for reunions and keeping his ties to the ALANA Cultural Center. One memory that continues to make him smile: He came back for reunion one year, walked into ALANA, and was greeted with the vision of Balmuth dancing with his wife. “I’ll never forget that,” he says.

A public thinker

“How well do you know other people? That’s an existential question that I think Jerry would find interesting to talk about,” muses Daniel Little, chancellor of the University of Michigan-Dearborn. Little came to know Balmuth quite well, he says, while teaching at Colgate from 1979 to 1996. When Little started as an assistant professor, Balmuth “was just so welcoming, and not in a perfunctory way. He was really interested in talking, in making me and my family feel welcome in Hamilton.” The two remained close friends as Little went on to become department chair of philosophy and religion, then associate dean of the faculty at Colgate, and when Little continued his career at other universities.

Little remembers Balmuth’s fascination with language — specifically how we convey meaning from one person to the other — similar to one of Balmuth’s philosophy heroes, Ludwig Wittgenstein. Akin to Wittgenstein’s “private language argument,” Balmuth believed language is inherently social and interpersonal.

“Jerry’s way of interacting with students, colleagues, and friends was that he was a very public thinker,” Little says. “He enjoyed talking and arguing — not in a legalistic way but exchanging and testing ideas. He was a public intellectual.” Little captured some of Balmuth’s contemplations in 2008 during a two-part video interview.

How would Little characterize the man of so many words in just one word? “Ebullient,” he says, “which I would describe as effervescent, always something to say, always in good humor.”

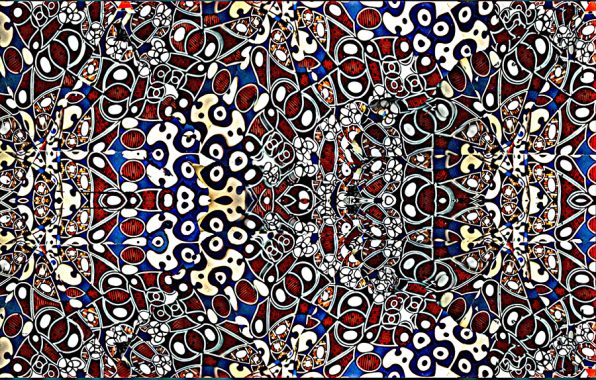

“I have applied the spirit of investigation and discovery as taught by Professor Balmuth” to my artwork, explains Stuart Zimmerman ’59, who had Balmuth as a professor when he was a first-year student.

“I have applied the spirit of investigation and discovery as taught by Professor Balmuth” to my artwork, explains Stuart Zimmerman ’59, who had Balmuth as a professor when he was a first-year student.

To create these works of art, Zimmerman starts either by painting a piece or using other imagery that he photographs through a kaleidoscope (which he himself manufactures). As a chemist at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, he created his earlier kaleidoscope work using objects like gemstones.

Balmuth, Zimmerman says, “served as an inspiration for his students to undertake alternate experiences to enrich their lives.”

Birthday tributes

In 2014, as Balmuth’s daughter Beth Raffeld was planning his 90th birthday celebration, she reached out to alumni asking for letters in his honor. More than 100 alumni responded. Here are excerpts from two letters:

My first introduction to Professor Balmuth was after becoming a philosophy major and learning that my father had had Professor Balmuth when he was at Colgate. I remember seeing him for the first time in the late 1980s and expecting him to be ancient (after all, my dad was almost 50 years old, for gosh sake) and being surprised that he appeared to be a similar age to my dad. Apparently my father had Professor Balmuth during one of his very first years at Colgate, when Professor Balmuth wasn’t that much older than his first students.I took Professor Balmuth’s course with my then boyfriend, now husband, Anthony DeFusto ’91. We sat next to each other in the front row and we were both in complete awe, sprinkled with a strong dose of intimidation. His teaching style was intense. He had a sixth sense of identifying students whose attention may have wandered for a moment and he would then call on that student immediately. Anthony and I sat at full alert, hoping only to not make complete fools of ourselves if we were asked one of Professor Balmuth’s famous probing questions.A few things were clear from the first day of class. First and foremost, Professor Balmuth was brilliant. Second, he had not only read the book being discussed, but by the condition of his book — full of comments and Post-it notes — it was obvious he was an expert on the reading. A visit to his office was even more intimidating because it was then that you realized that he had not just read a few books with such intensity but that he had read hundreds of books with that intensity.

Even as Professor Balmuth ascended to a god-like status in our minds, spotting him at the Hamilton movie theater enjoying a popular film while chewing contentedly on Jujubes humanized him a bit in our eyes. Although it made his intellectual status even more impressive realizing that he was also just a mere mortal like the rest of us. It was hard to believe that the same man who taught us about Buridan’s ass enjoyed Lethal Weapon.

“We were both in complete awe, sprinkled with a strong dose of intimidation.”

Anthony and I were making it through the semester without much humiliation when one day we passed Professor Balmuth on the Quad. We were holding hands, and Professor Balmuth acknowledged us and smiled. Shortly after, it was a visiting day for parents, and they were invited to sit in on their children’s classes. My parents greeted Professor Balmuth and took their seats in the back row. It just so happened that we were studying a passage that included a section on the definition of love. Professor Balmuth called on me to read the section aloud. He then proceeded to alternately ask Anthony and me questions on this section, much to our complete horror. Somehow, we couldn’t help but admire his mischievous sense of humor. Anthony and I both became teachers and we fully appreciate that having fun during the job is essential, and sometimes the most fun isn’t necessarily fully appreciated by the students at the moment.

We don’t go a day without being thankful for all we learned at Colgate. We had awesome (in the literal sense of the word) professors, with Professor Balmuth being the most awesome of them all. Those professors taught us how to think deeply, and we use those skills every day. From Professor Balmuth, we also learned humility about how much there is that we don’t know, as well as how much wisdom one person can acquire.

— Elizabeth Tarvin ’92

In the Platonic dialogue Laches, Socrates focuses his thought on the meaning of courage. Together with friends and acquaintances, including two generals in the Athenian army, the discussion centers on various definitions of courage, and the relationship between this quality and other aspects of virtue such as wisdom and justice.A superficial reading of Laches suggests the two generals are unable to define the nature of courage. Socrates even says as much in the text. A critical analysis of the dialogue, however, reveals a much different understanding of their efforts. For those who look beneath the surface, there emerges a powerful and coherent understanding of courage, and the way this quality relates to other universal ideas.

“There was always the sense that Balmuth and his students were engaged in something important.”

According to Plato, courage is the rational and unending pursuit of truth, wherever it may lead and whatever its consequences. It is the use of the dialectical process to question assumptions, destroy illusions, and challenge beliefs, lest we mistake the truth for that which is not.

Within this Platonic understanding of virtue, Jerry Balmuth is the most courageous man I know.

The standard of excellence he brought to the classroom, and the university community at large, was uncompromising. His classes were not lectures on meaning, but explorations of meaning, and this distinction made all the difference in creating a learning environment that was challenging, vital, and creative.

From Core 170-180 to the senior seminar on Wittgenstein, there was always the sense that Balmuth and his students were engaged in something important, and that insight into meaning was possible for everyone who cared enough to become part of this dialectical process.

The Laches ends with Socrates advising his friends that education never ends. This realization, perhaps more than any other, captures the essence of why Jerry Balmuth matters so much to those of us who were privileged to be his students.

Plato has Socrates as the teacher who champions the pursuit of truth. Colgate University has Professor Balmuth.

— Vincent Brocki ’75

The Jerome Balmuth Award for Teaching and Student Engagement

Balmuth’s professorial legacy lives on through the Jerome Balmuth Award for Teaching, established in 2009 by Mark Siegel ’73 to honor “a faculty member whose teaching is distinctively successful and transformative, recognizing that such distinction can be achieved through a broad spectrum of methodologies ranging from traditional to innovative.” Former students, friends, and family members also endowed the Jerome Balmuth Fund (which supports visiting speakers and enhances the outreach of the philosophy department) and the Balmuth Endowed Scholarship Fund.

“For me, the most important aspect of Colgate was the commitment professors had to their students getting a fine education,” says Siegel, a philosophy major who is now president of ReMY Investors & Consultants. “And by that, I mean not just teaching Plato or a particular topic, but helping them get a real understanding of the human condition as each of the great thinkers had considered it — to broaden students’ thinking and awareness.”

By naming the award after Balmuth, Siegel was honoring his mentor: “Jerry stood out as one of those who was a great teacher.”

As other alumni often recall, Siegel remembers Balmuth as a challenging professor. “He was not a person to suffer fools gladly,” Siegel says. “He wasn’t mean, but if somebody said something that was not sensible or on point, he would let the person know that it wasn’t a good answer.” Balmuth didn’t just expect the most out of his students for the sake of being difficult; he wanted to educate and prepare his students. In return for his students’ commitment to their work, he dedicated his time to their work. For example, when grading papers, Balmuth wrote extensive notes so students “knew he read it carefully and thoughtfully and that he had put as much effort into it as you had,” Siegel says. “And he would talk with you about what he saw and what you did, which I thought was incredibly helpful in my growth as an educated person.”

In 2010, the inaugural award went to Marilyn Thie, professor of philosophy and religion and women’s studies emerita. She was one of the university’s first female faculty members when she joined Colgate in the mid-1970s. Other recipients have included Anthony Aveni, Russell Colgate Distinguished University Professor of astronomy and anthropology and Native American studies emeritus; Margaret Maurer, the William Henry Crawshaw Professor of literature; and, most recently, Frank Frey, professor of biology and environmental studies.

“I think teaching is important,” Siegel says. “There’s almost nothing in the world I have done that I have been as proud of as this award.”

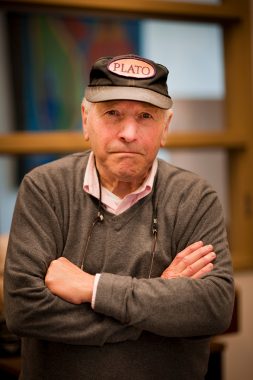

Thinking cap

Balmuth with grandson Eli Raffeld ’10 and granddaughter Miriam Raffeld

Balmuth’s trademark accessory was his Plato hat, which his daughter Deborah bought him in the mid-’80s. Her dad always wore hats, she says: “I think it was his version of a yarmulke.” So, when she found a Plato cap at the Harvard Square Booksmith, she knew “it was so perfect with the name of one of his heroes on it.”

In the beginning of his talk “Why we should read Plato,” Balmuth explains further: “People ask me why I wear this hat, and the answer is, it’s a billboard for Plato. Because I believe both in philosophy as the most profound and critical subject that one can engage in and also as Plato as the central focus, the seminal thinker in the philosophical tradition.”

Through the years, the professor collected hats with other philosophers’ names on them (although he mostly donned the Plato cap), and in celebration of Balmuth’s 50th year of teaching at Colgate, the Department of Philosophy and Religion had maroon “Balmuth” baseball caps made. His colleagues can still be seen wearing them around campus. As for Balmuth, his Plato cap is buried with him in the Colgate cemetery.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pfy8U1tbmI4?rel=0&w=560&h=315]

A 55-year mentorship

Karl Baumgartner ’65 says he had his ups and downs as a student. But Balmuth, as his professor during his first year and adviser for four years, was a steadfast supporter. Even when Baumgartner left school for a semester, Balmuth corresponded with him and encouraged him to return to Colgate.

“He was a mentor all the way through,” Baumgartner says. The two stayed in touch, writing letters right up until Balmuth’s death. These two letters encapsulate their relationship. The letter from Balmuth to Baumgartner was his last to his former student.

Here, too, Balmuth will have the last word.

April 14, 2014

Hi, Mr. Balmuth,

Well we’ve known each other 50 years and we’ve stayed in touch throughout. That’s a pretty good accomplishment.Of course I’ve always known that I got the better end of this deal, I the student, you the mentor. Over the years I’ve wondered how my life might have turned out differently had it not been for the arbitrary circumstance that I was placed in your Core 13 class in 1961 and you were assigned as my adviser. I think possibly quite a lot. For one thing, it is unlikely that I would have majored in philosophy had you not made it so interesting and challenging. When I arrived from Oklahoma in 1961, I certainly didn’t contemplate it as a major; I was barely familiar with it as a discipline.

But I believe the philosophy major has distinctly impacted my life. Personally it has contributed to the shaping of my intellectual beliefs, my perspectives, my ethical foundation. And professionally it benefited my critical thinking and gave me confidence that analytically I was better prepared than others.

Some of the first concepts you exposed us to are indelibly retained. “I’m not wise, but I’m wiser than you because I know I’m not wise.” “I think, therefore I am.” “The unexamined life is not worth living.” And you made it such a challenge. I still remember Core 13 vividly. The thinking, the conceptualization, the challenge, the excitement. I took notes diligently and studied intently for days prior to the semester final, and was apprehensive awaiting my semester report card. It arrived in my little mailbox at the student union, and included Philosophy & Religion: B+. I thought, “That means I must have gotten an A on the final!” It is the single academic achievement of which I remain the proudest.

For me, another bit of serendipity was your ability to understand the students. You might recall I suffered a major sophomore slump. I was called on the carpet by Dean Griffith. He told me to go speak to my adviser. I went to your office, not for the first time; I talked, you listened. You told me that when I returned to Colgate you would allow me to submit an overdue paper for which I had received an incomplete the previous semester and was still carried as an “I” on the books…

So now we enter our golden years and look back. Congratulations on a wonderful and meaningful life. You have given much but no doubt at the same time received much. As my friends get older many are considering their legacy, what kind of footprint they will leave, what might they do now to have an impact. That is a consideration that you don’t have to dwell on. You know the impact you made on me and countless other students over the years, and moreover the impact doesn’t end there. It is carried on in bits and pieces through our children and those whom we have influenced in our lives. It is a pretty large chain.

Karl

Dec. 30, 2016

Dear Karl,

You comment on the serendipity of our friendship since you could have easily been assigned a different section and our lives been different, and I would have been bereft of the special sense I have that we’ve sustained a bond that goes beyond a particular classroom experience. For this gift, I need to thank you … and I do … since it is your persistence and determined follow-up that has sustained our relationship and developed into friendship and concern! Along with your other remarks about your education at Colgate, you comment on the effect my teaching had on you and possibly other alums. I appreciate these comments since they point to whatever strengths I have as a teacher as distinct from whatever skills I may have as a writer or scholar or philosopher. The fact is that the classroom was my self-teaching and discovery period; even more emphatically, it was the occasion when I, with the class, were really thinking fresh thoughts and developing new ideas — special insights — on old, often classical questions. The class was where the text — a classical text usually — was confronted by the student, challenged by and challenging the teacher and the class to find an insight or the special truth, which made it a classic text worth re-pursuing in class. What was attractive to me, and possibly to some of my students, was the rehearsal and understanding of much older thoughts now in new circumstances … a rethinking from a new perspective, of those discoveries and important ideas tied to the tradition of thinking scholars about the human condition … religious, ethical, epistemological, and scientific … facing the way things are and are not! To bring Socrates back into our thoughts challenging the “unexamined” life was, for me, to revitalize a dead history into a live and exciting provocation, experiencing what earlier provoked other minds.The classroom was then, for us, the laboratory for the mind; and I tried to bring the student with me, often further than they (or I) were often willing (or able) to go; and while some hung back, I was always grateful for students like you who took the challenge and went along, if not convinced or understanding, seeing it even as a game, ultimately recognizing that the intellectual journey was, in the long run, an exciting challenge and ultimately worth the while! Exploring intellectual geography in the effort for enlarging thought beyond the mundane and immediate, engaged in producing and living new thoughts … actually discovering new worlds!

So thanks for your friendship, Karl. It’s been good for me and I hope for you as well. You have been a student who did (and does) the work of provoking new thoughts, new language, which open new ideas and new opportunities for the mind.

Jerry

“The classroom was then, for us, the laboratory for the mind; and I tried to bring the student with me.”

— Jerry Balmuth, Harry Emerson Fosdick Professor of philosophy and religion emeritus