1955 Elvis Presley was taking the Louisiana Hayride to fame, polio met its match with the Salk vaccine, Jim Henson gave birth to Kermit, and Dwight Eisenhower became the first president to hold a televised news conference.

On the radio waves, more than 2,281,000 weekly listeners were tuning in to College Quiz Bowl, launched two years earlier.

When NBC invited Colgate to participate, “it was a big deal,” remembers team member Jim Wachtel ’55.

When NBC invited Colgate to participate, “it was a big deal,” remembers team member Jim Wachtel ’55.

The chapel filled with eager students that spring, rooting on the Raiders as they were connected through a radio hookup with their opponents, who were on their own campuses, and with host Allen Ludden, who was in a New York City studio.

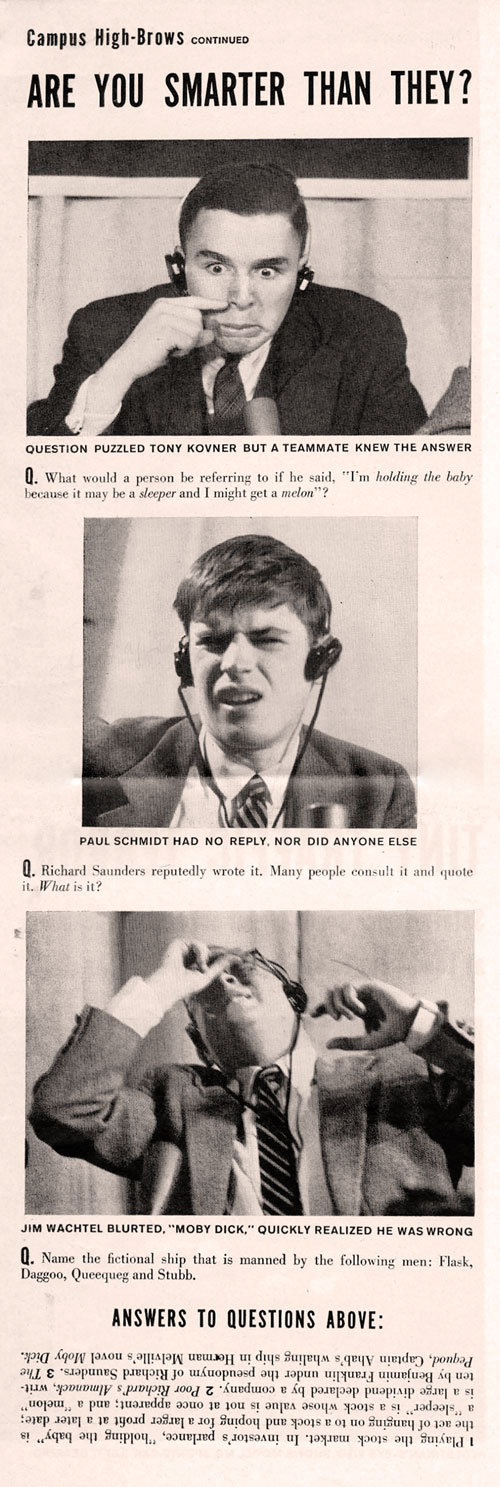

Colgate was on a roll when Life magazine featured the match against Cornell. In its article titled “From Campus High-Brows to Campus Heroes,” Life noted that, for the 50 competing colleges, the quiz bowl had become as exciting as a football game, “converting college eggheads into campus heroes.”

Wachtel, one of those braniacs-turned-big-shots, recollects:

One evening, in February 1955, during my senior year, I walked into the dorm lounge where a group of about 10 or 12 students was seated in a circle attempting to answer what we would now call trivia questions. After I’d joined in, Keith MacGaffey ’55 commented, “You’re very good at this.” I responded, “Thank you, but what are we doing?” Keith explained that NBC had invited Colgate to enter a team for the College Quiz Bowl program and that I had walked into an unofficial practice session. He suggested I come to the practices, which I did for the next three sessions. A four-man team was to be selected by a vote of the participants. After the voting, the team was made up of Paul Schmidt ’55, Peter Gould ’56, Marty Heyert ’56, and myself. I am the only surviving member.

Lloyd Huntley ’24, student activities director, provided suggestions for studying and conducted the weekly practices. During the practice sessions, we answered questions and Huntley kept track of the percentage each participant answered correctly. Before we voted, he distributed that data. He did a fine job in organizing the team.

Our first match was against Mount Holyoke in March. Each team was at its own campus, and quizmaster Allen Ludden was at Radio City in New York City. Although we couldn’t see the other team, we could hear their responses. The score was announced several times during the competition. At Colgate, most of the matches were held in the largest venue on campus, the chapel, which held 1,200 seats, most of which were occupied during the matches.

“What animal was known to the ancients as the camelopard?” My first thought was, “This is hopeless; we’re going to lose.”

— Jim Wachtel ’55

Contestants had buzzers to signal that they wanted to answer a question; the first person to signal had the first crack at the question. If the individual’s answer was correct, that team was eligible for a bonus question on which the team members could confer. If the answer was incorrect, the other team was given an opportunity to respond.

The last answer of the first match was the most outstanding of the series, in my opinion. When Ludden announced that the time was nearly up, we had a small lead. The question was: “What animal was known to the ancients as the camelopard?” My first thought was, “This is hopeless; we’re going to lose.” I was greatly relieved when Paul Schmidt answered, correctly, that the camelopard was the giraffe. When the program ended seconds later, we gathered around Paul asking, “How did you know that?” He told us he didn’t know it, he had figured it out. “Pard,” he told us, “means a spotted animal. For example, the leopard is a spotted lion. So I thought, ‘What animal would be a spotted camel?’ and it had to be a giraffe.” I’ve always believed that being able to figure out an answer should be worth more credit than knowing an answer outright.

Nowadays, I would hesitate to answer a question on the basis of as little knowledge as I had about some of those subjects, but in those days, taking a guess seemed to work well. For example, “What did these men have in common: Brewster, Bradford, and Winslow?” I answered that they all were Pilgrims from the Mayflower. I was pleased that although the official answer was that they were all signers of the Mayflower Compact, my answer was acceptable.

Nowadays, I would hesitate to answer a question on the basis of as little knowledge as I had about some of those subjects, but in those days, taking a guess seemed to work well. For example, “What did these men have in common: Brewster, Bradford, and Winslow?” I answered that they all were Pilgrims from the Mayflower. I was pleased that although the official answer was that they were all signers of the Mayflower Compact, my answer was acceptable.

Our third match was against Cornell, and we were told Life magazine was going to cover it. They sent out three teams of photographers, one to Colgate, one to Cornell, and one to NBC’s New York City studios. The photographer at Colgate took approximately 300 photos during our match. He had 10 Leica cameras, which he reloaded on the fly.

In that match, Ludden asked, “Name the fictional ship that is manned by the following men: Flask, Daggoo, Queequeg, and Stubb.” I meant to say, “That’s in Moby Dick. The ship is the Pequod,” but what came out was, “That’s Moby Dick.” As soon as I realized I had answered incorrectly, I threw back my head in disgust, and as I did so I thought, “I’m going to be in Life magazine” — and I was, on page 104 of the April 4, 1955, issue. Schmidt, our leader, was irked, too, because he missed a question and there’s a picture of him looking like he was about to die. We felt that, to read the article, one would think Colgate had lost instead of trouncing our opponent.

“Name the fictional ship that is manned by the following men: Flask, Daggoo, Queequeg, and Stubb.” I meant to say, “That’s in Moby Dick. The ship is the Pequod,” but what came out was, “That’s Moby Dick.”

— Jim Wachtel ’55

The night we went up against Duke in our fourth game, we were displaced from the chapel because a sold-out Boston Pops concert was scheduled there at 8 p.m., just as our broadcast ended. We were told to go to the back door of the chapel so that after the first number was finished, we could be escorted to front-row seats saved for us. As the second half of the concert started, [conductor] Arthur Fiedler announced our winning score in his charming European accent. The audience roared — and we felt just great.

When our loss to Mt. Holyoke ended our College Quiz Bowl run in April 1955, we had a record of five victories and a final defeat. We won against Mt. Holyoke, Columbia, Cornell, Duke, and Georgetown before losing to Mt. Holyoke in a second match. Except for the two close matches with Mt. Holyoke (one victory, one defeat), the matches were very one-sided.

After each match, Good Housekeeping magazine donated $500 to the winning college. Colgate asked the team to decide what their winnings should be used for. Because the university would be replacing the old library with a new building, the team voted to donate its $2,500 in winnings to the building fund. Coincidentally, $2,500 was the amount needed to have a study carrel in the new library, named for the team.

Photo by Dick Broussard

We are the champions

Quiz bowl returned bigger than ever in 1959 when CBS took the competition to TV. Between six to 10 million people watched The G.E. College Bowl every week. Sponsor General Electric shelled out $1,500 for each victory, to be applied to the winning school’s scholarship fund.

Colgate declined an invitation the first year because the event coincided with commencement, but the following year, the Raiders took the game by storm. For six Fridays that spring, they flew down to New York City on an all-expenses-paid trip. “Imagine … staying at the Biltmore, room service for champagne and caviar, free tickets to popular shows, free dining, whatever we wanted,” recalls team member William McDonald ’61.

The Raiders handily defeated five colleges, starting with New York University and finishing off with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The rules designated that a school had to retire after five wins, and Colgate was the first to win five in a row. “The show had been on TV for five years and nobody else had done this,” says team member Richard Grote ’63. Retiring undefeated earned the team an extra $1,500 ($3,000 total for that match). This brought their total winnings to $9,000. But the Raiders weren’t done yet.

“It was really a speed game, not a knowledge game.”

— William McDonald ’61

CBS announced a playoff round for the following October. Colgate was to take on Rutgers, for a prize of $3,000. Led by William Thoms ’61, the Colgate team included Grote, McDonald, and Stephen LeFrak ’60. They sported suits and ties, as well as “Kennedy for President” buttons, which incurred the ire of the G.E. vice president at the time. In fact, afterward, he threatened that Colgate would never again have the chance to appear on The G.E. College Bowl.

During the game, this was unbeknownst to the four Colgaters, who were already fighting to overcome their nerves. “The pressure was unbelievable,” Grote says. As the host explained the rules, Thoms bounced and shifted in his chair. Grote yawned and took deep breaths, looking like he was on the verge of throwing up. After a commercial break advertising G.E.’s “first push-button clock radio with snooze alarm,” the questions began. Rutgers got the first one right. Then, on the toss-up question, Colgate’s Thoms buzzed in and answered correctly. LeFrak patted him on the back, and the team became energized.

“It was really a speed game, not a knowledge game,” McDonald said. “[Thoms] was so confident that he would sometimes hit the response button before he quite knew the answer to the toss-up question, knowing that in the split second while his name was called, he would remember it. As a result, our team got most of the toss-up questions, giving us sole access to the bonus questions and preventing the other team from scoring.”

“It was really a speed game, not a knowledge game,” McDonald said. “[Thoms] was so confident that he would sometimes hit the response button before he quite knew the answer to the toss-up question, knowing that in the split second while his name was called, he would remember it. As a result, our team got most of the toss-up questions, giving us sole access to the bonus questions and preventing the other team from scoring.”

At the first half, the score was Colgate 100, Rutgers 60. A commercial introduced the G.E. Twin Power cleaner, Ludden briefly chatted with the teams, and footage from the previous night’s football game played. Although Rutgers beat Colgate at pigskin, they couldn’t catch the Raiders at quiz bowl. The final score was Colgate 185, Rutgers 125. A commercial for the miniature snooze alarm clock aired, and the Raiders put their quiz bowl run to rest.

With a total of $12,000 in prize money, the team designated their winnings to start a scholarship fund for students from Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). It was the team’s idea in order to bring international students to campus and introduce Colgate students to new cultures. Also, because Northern Rhodesia was in a period of transition, the university was in a position to “contribute to the education of leaders and aid in the growth of this nation,” according to a Maroon article. Others helped to grow the fund, which brought three Northern Rhodesian students to campus the following year.

Watch the 1960 playoff game against Rutgers

A valiant effort

Invited back on the scene in 1969, Colgate enjoyed a brief stint of success as that team triumphed in its first two games. Composed of Joseph Baldanza ’72, Robert Diamond ’70, Warren Joseph ’70, and William Mendez ’72, the team defeated Trinity University and then the University of Illinois.

For Mendez, the highlight was the G.E.-sponsored trips to New York City, especially the tickets to any Broadway show of their choice (he saw Hair). Also, Colgate broadcast the shows in the dining hall during Sunday dinner, “so on Monday morning, people were slapping me on the back,” Mendez recalls. “I got to be a big man on campus instantly as a freshman, which was nice.”

Unfortunately, they fell in their third match, against Davidson College. “It was a letdown,” says Baldanza (who later got another shot at trivia fame when he appeared on Jeopardy in 1987).

From their first two victories, the team totaled $7,000 in prize money. They voted to give their winnings to the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Fund (a Colgate-endowed scholarship).

Rather than receiving silver bowls, as previous teams had for their wins, the 1969 team members could have their pick of a G.E. product. “I asked for an electric toothbrush,” Baldanza remembers, “but I never got it.”

Photo by Alyssa Schukar. (L to R): Malachi Jones ’20, Justin Mailom ’20, Cameron Pauly ’19, and Gavin Gao ’19

The new wizards of wit

Gavin Gao ’19 and Cameron Pauly ’19 met, where else, but through trivia night on campus. Pauly wasn’t actually at Donovan’s Pub that night, but Gao played with Pauly’s roommate and learned that Pauly, like Gao, was in competitive trivia as a high schooler. There was no question that the two would become friends and restore the quiz bowl tradition at Colgate.

In the club’s first year, they’ve attracted 10–12 regular members but are hoping to spread the word and grow. “Everybody has knowledge that’s useful,” Gao said, because of the multifarious topics covered in competition.

“I think the reason Colgate’s done so well this year is we have the core curriculum, and that goes a long way in giving people a breadth of knowledge.”

– Gavin Gao ’19

“At practice, people are surprised at what they know. [For example,] they didn’t know that Nirvana was relevant,” Gao added. “Or something they learned in class,” Pauly chimed in. (The synced-up friends have a habit of finishing each other’s sentences.)

This year, the group participated in five competitions and earned a bid to participate in the Intercollegiate Championship Tournament (ICT), held in Chicago in April 2017.

This year, the group participated in five competitions and earned a bid to participate in the Intercollegiate Championship Tournament (ICT), held in Chicago in April 2017.

The quiz bowl format has stayed much the same over the years: participants still ring in with handheld buzzers, and making an educated guess continues to be a popular strategy. But the competitions are less glamorous than the G.E. days. This year’s group flew to Chicago with their club funds; they weren’t offered free Broadway tickets or caviar; and there was no prize money.

Even so, Gao and Pauly were happy to have made it as far as they did. “Despite being a new club, despite having new members who have not done trivia at the college level before, we were still able to do very well at all of our tournaments, make it to nationals, win sectionals, and place well individually,” Gao said. “I think the reason Colgate’s done so well this year is we have the core curriculum, and that goes a long way in giving people a breadth of knowledge.”

At ICT, the group finished 26 out of 32 Division II teams, but “going to nationals at all in our first year was an impressive feat,” Pauly said. Their favorite moment from the tournament? Going buzzer to buzzer with the University of Chicago, which was ranked one of the top four teams and came in seventh. “We were the only team to beat them that finished outside of the top five,” Pauly said. “It was quite an upset,” Gao emphasized.