How do you change into

the person you know you are?

Chris Edwards ’91 explains in his new memoir,

BALLS: It takes some to get some.

I came out to my grandmother when I was 5. I just didn’t know I was doing it.

Neither did she.

I can’t tell you what Gram was wearing at the time, but I’m sure it was something fashionable, which likely meant one of her bell-bottom pantsuits and a wrap turban with some bright, crazy pattern on it. Her mother, my Great-Gram, was the matriarch of our family and owned a summer cottage on Cape Cod that served as the hub of our extended family gatherings from July through August. Because Great-Gram’s house was a short walk to Old Silver Beach, it wasn’t uncommon to find six or seven of my relatives’ cars wedged in like a jigsaw puzzle on the front lawn (and by lawn I mean crabgrass). On this particular day, my parents’ wood-paneled station wagon was wedged in among them. Gram had driven down with us, which always made the 90-minute ride more fun, and as usual, my older sister, Wendy, and I fought over who got to sit next to her. There was only room for three people in the backseat, so with Grampa up front with Dad, and Mom in the back holding my baby sister, Jill, that meant one of us was destined for isolation in the way back. Still, Gram kept us both entertained by playing “I Spy” or having us compete to see who could spot the most VW bugs…

Gram loved the beach and once she gathered up her necessities —aluminum folding beach chair, sticky bottles of suntan oils, and rubber swim cap dotted with plastic daisies to protect her frosted hair — she walked us down to Old Silver where we spent the whole day taking in the sun. With both sides of my family being Armenian, most of my relatives had dark hair, brown eyes, and olive skin like Gram’s that tanned easily. Wendy and I fit the bill. But it was sunblock slather sessions for Jill, who was inexplicably born with light brown hair, blue eyes, and fair skin. (We’d later tell her she was adopted and that the pale Ukrainianman who delivered Mom and Dad’s dry cleaning was her real father.)

After a full day at the beach, Wendy and I were back at Great-Gram’s house in our T-shirts and shorts, hair still wet from the outside shower. We sprawled out on the faded Oriental rug in the family room with our coloring books and crayons, while Gram repeatedly passed by us on her route from the kitchen to the dining room carrying platters of shish kebab, salad, and pilaf.

On her last pass, she yelled, “Come on, girls, dinner’s ready.”

Wendy immediately sprang up and followed her to the table. I didn’t flinch. I honestly didn’t think she was talking to me. Soon Gram was back kneeling across from me at eye level.

“Didn’t you hear me calling you?” she asked.

“No.”

“I said, ‘Come on, girls.’”

“I’m not a girl,” I replied, insulted.

“Yes . . . you are,” she said gently.

“No, I’m not. I’m a boy.”

“No, you’re not, sweetheart.”

“Well, then I’m gonna be,” I insisted.

“You can’t, darling,” she said, then smiled sympathetically and walked back into the kitchen.

I’ll show her! I thought.

Since everything about me was boy-like — my clothes, my toys, my obsession with all superheroes except for Wonder Woman and her lame, invisible plane — I put my 5-year-old brain to work and determined that the only thing lumping me in with the girls was my hair length. Girls had long hair; boys had short hair. So to clear up Gram’s and anyone else’s future confusion on this matter, as soon as we got back home from the Cape I told my mom I wanted my hair cut “like Daddy’s.”

Many moms would have said “no way” to such a request, but my mom wasn’t too concerned with gender stereotypes. “Nano,” as friends and family called her, may have been traditional when it came to family, but she was relatively hip as far as moms went. She had given up her career in nursing to stay home and raise three kids while my dad worked his way up the ladder in advertising. She was extremely involved in our school activities from kindergarten through high school and was known as the “fun mom” who would plan the best birthday parties and supply endless trays of snacks and candy whenever friends came over. She’d even let us watch scary movies, though usually to our own detriment. Seeing Jaws at age 7 led to an entire summer on dry land. Forget swimming in the ocean; I wouldn’t even go near a pool. What if the shark came up through the drain?

Mom wasn’t — and still isn’t — a big skirt or dress wearer, so she never put Wendy or me in anything particularly girly when we were little — only Jill, whose favorite colors were pink and purple. Wendy and I were both tomboys. For us, it was Osh Kosh overalls in neutral colors, Levi’s corduroys, and “alligator” shirts. So when I asked to get my hair cut short, Mom took me to the barbershop in the center of town. After that, sure enough, everyone outside my family started calling me a boy.

Problem solved.

See, Gram, that wasn’t so hard.

It wasn’t until the following summer that I realized I was lacking certain “equipment.” Still sandy from the beach, Wendy and I were eating popsicles with our younger cousin Adam on Great-Gram’s back deck, a danger zone for bare feet. I was standing on my wet towel in an effort to avoid another painful splinter-removal session with Mom’s sewing needle when Adam nudged me and said, “Watch this.” He then turned his back, and a stream of what I thought was water came shooting out of his red swim trunks over the deck rail in a perfect arc.

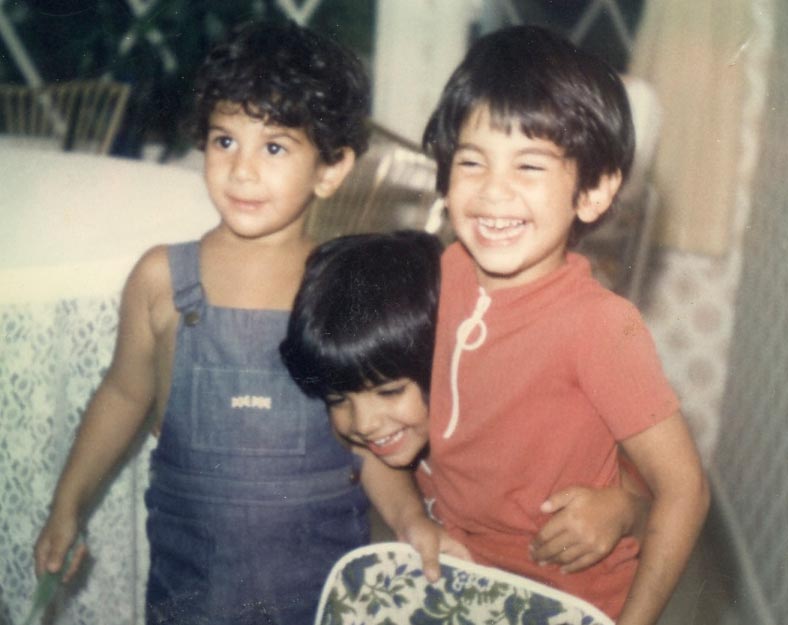

Chris, in red, with his sister Wendy and cousin Adam

I was in awe. “How’d you do that?” I asked. “Do you have a squirt gun in there?” Wendy, 17 months my senior and always ready to educate (she dropped the “there is no Santa Claus” bomb on me seconds after finding out the awful truth), fielded the question quickly and effortlessly in a “could-you-be-any-dumber?” tone.

“It’s not a squirt gun. He’s peeing.”

How was this possible? When I peed it went straight down and I had to sit.

“But how does he get it to go up like that?”

“Because he has a pee-nis.”

This answer only raised more questions in my mind: What is a “penis” and how come I don’t have one? I was too embarrassed to ask and something told me I didn’t want to know the answers, for fear they would only lead to more evidence that Gram and everyone else in my family was right: I wasn’t a boy like I thought — not even with my short haircut. It was easier to talk myself into believing my penis hadn’t grown yet than to face that possibility. So every night I prayed that my body would change into a boy’s body. That I would grow a penis — whatever that was — and everyone would finally realize they were wrong for thinking I was a girl.

Well, my body changed all right. Just not in the way I’d hoped.

Puberty struck, and it betrayed me in the worst possible ways I could imagine. First, two buds began to protrude from my formerly flat chest, so I wore extra layers of clothing to hide them from myself and everybody else. I couldn’t think of anything more traumatizing than having to wear a bra, let alone shopping for one.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

It happened the summer after my 12th birthday on a fittingly stormy summer night. My family now had our own cottage in Old Silver Beach Village, directly across the street from Great-Gram’s house. While Jill had her own room, Wendy and I shared the larger front bedroom with its wood-paneled walls, cooling cross-breeze, and “magic” closet that you could walk into, turn a corner, and wind up in my parents’ bedroom. The house had only one bathroom, which was decorated in a nautical theme and centrally located at the top of the stairs. It was so small you could sit on the toilet, stretch your legs out, and rest your feet on the tub. The living area was divided into a family room where we’d watch TV and a sunroom where we kept all our toys and games along with a bright green folding card table, the one piece of furniture in the house that got the most use.

Wendy and I were babysitting Jill and our cousins Adam and Dana while our moms were out bowling. The five of us were at the card table embroiled in yet another never-ending game of Monopoly. Looking past our reflection in the darkness of the picture window, I could see the rain coming down sideways in the glow of the street lamp, the sound of thunder getting closer and closer. Since everyone was focused on the lopsided trade Wendy was trying to con Dana into, I decided it was a good time to run upstairs for a pee break. And that’s when I saw it: the red splotch.

I froze, my mind flashing back to the movie I had been forced to watch with all the girls in my fifth-grade class. My first thought was, This can’t be happening. Wendy’s older than me. She’s supposed to get it first.

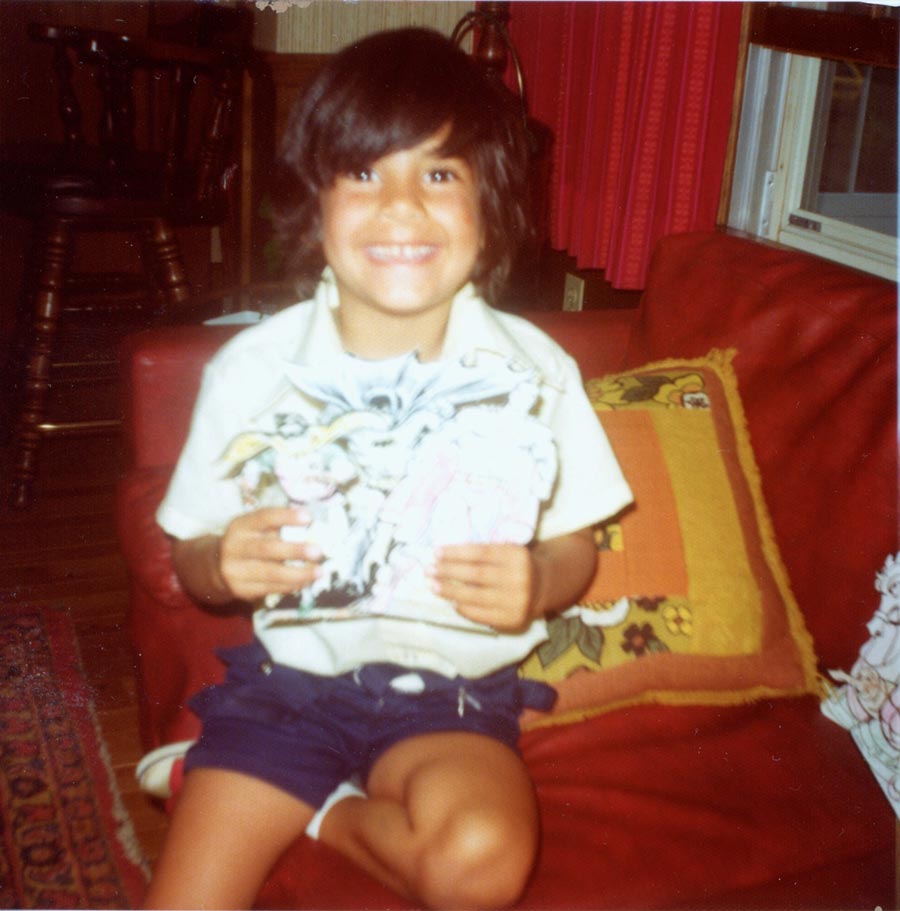

Chris with his super heroes — “an obsession”

My second thought was, I’m doomed.

A loud clap of thunder crashed as if to accentuate the horror of my situation, followed by playful screams from below. I didn’t know what to do so I began frantically stuffing the crotch of my underwear with toilet paper, the escalating storm echoing my panic. I walked downstairs with the gait of someone who’d just ridden his first rodeo to find my sisters and cousins staring out the window as a lightning bolt struck the telephone pole across the street. The lights inside the house flickered. They all screamed in unison, more out of excitement than fear, while I sat there trancelike on the couch. Just then, my mom and her sister burst open the door, soaked from the rain. Sensing what was to come, Mom rushed to the kitchen to find a flashlight and some candles while Aunty Barbie headed for the sunroom. Within seconds, another bolt of lightning struck and the whole house and street went dark. More playful screaming like what you’d hear on a roller coaster filled the room, only to be drowned out by uncontrollable sobbing. My aunt followed that particular sound to the couch and, after whacking her shin on the coffee table, felt her way to my shoulder and put her arm around me. “It’s okay, don’t be scared, Jilly.”

“I’m over here!” Jill shouted from across the room. The surprise in Aunty’s voice when she realized it was the 12-year-old, not the 9-year-old, that she was consoling only made me feel worse. I wanted everyone gone so I could talk to my mom privately. Once she came in with the flashlight and began lighting candles, I took one up to my bedroom and waited for everyone to leave. When I finally heard the front door shut, I stood at the top of the stairs and called for her. Halfway up, she saw me looking down at her in tears.

“What’s wrong?” she said, seemingly annoyed that her 12-year-old was afraid of the dark.

“I got my period,” I eked out. “What do I do?”

Mom seemed just as caught off guard as I was. She, too, expected Wendy would go first. She ushered me into the bathroom and looked inside my underwear to make sure. Her face softened and then she disappeared to the linen closet while I stood there helpless, looking through the crack in the doorway as Wendy and Jill hovered outside it trying to find out what was going on. Soon Mom returned with some maxi pads and a fresh pair of underwear and closed the door behind her. I couldn’t speak. I knew my mom was talking, but I couldn’t hear what she was saying over the sound of my whole world crashing down on me. I climbed into bed with what felt like a diaper between my legs and cried myself to sleep, quietly so my sister wouldn’t hear.

In one night, any hope I had left of being the boy I knew I was evaporated. No matter how much I prayed, I was stuck with this body — stuck being a girl.

In one night, any hope I had left of being the boy I knew I was evaporated. No matter how much I prayed, I was stuck with this body — stuck being a girl.

Rebirth

Chris Edwards ’91 is transgender — but that doesn’t define him. He’s a successful advertising executive, a son, a brother, an uncle, a former rugby player and sorority sister, a people person who makes friends easily, and a type A-plus perfectionist. Currently, he’s an author who is telling his story in a candidly funny — sometimes outrageous — way.

“No, I’m not just really really gay,” is one of the chapters in his new book — BALLS: It Takes Some to Get Some — as well as “Bye bye boobies” and “Take my uterus. Please.” He’s frank about growing up with a tortured sense of self, and the book sheds light on some of his darkest moments. But the reader is buoyed by the levity in Edwards’s storytelling, bringing us along like a close friend in whom he’s confiding.

“I’m an ad guy, so I write like I speak,” he said. “I wanted it to be engaging and entertaining so that people read it and then walk away being more informed on this topic.”

In the book, he’s open about the challenges he’s faced: feeling like he was dressing in drag every time he was forced to wear a skirt for church, explaining his feelings to people without the words that today are part of the general lexicon, dating disasters, and the psychological and surgical rigmarole he’s endured to have a body in which he feels comfortable.

“Gender is not defined by what’s inside your pants;

it’s defined by what’s inside your brain.”

Dedicated to his family, the book describes his parents not just as characters in his narrative, but also as characters. Edwards’s stories about them reveal the source of his wry sense of humor. More importantly, we learn that they also gave him tremendous support. Growing up transgender is no laughing matter, and Edwards proves that family makes all the difference.

“While numbers are hard to quantify, studies suggest that nearly sixty percent of transgender teens go without support from their families, and in those cases the risk of suicide is much higher,” he explains in the epilogue. “The sad fact is that more than fifty percent of all transgender teens will attempt suicide. And without parental support, many of them will succeed.”

Edwards writes about his own thoughts of suicide — a plan, actually, that he’d been devising since high school to kill himself after college. “I couldn’t continue pretending to be a girl much longer; keeping up my act was exhausting,” he writes. “And to what end? When I looked to the future, all that was in store for me was more misery. Well, except maybe for college. That was supposed to be a blast.”

At Colgate, he did embrace the experience. He joined a sorority — “my best friends were in it, and they were the fun people” — and the rugby team — “a diverse bunch.”

Still, “there was no LGBTQ community” back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Edwards recalled. “I didn’t know anyone who was even openly gay. It was not socially acceptable.” He had to hide his true self and the fact that he was falling in love with a close female friend.

Issues of what he’d later learn to call gender dysphoria (an unease with having the physical characteristics of one’s gender, accompanied by identification with and desire to live as the opposite gender) had yet to enter public consciousness.

“I know now what I didn’t know then: sexual orientation and gender identity are two completely separate things,” Edwards explains in the book. “Gender is not defined by what’s inside your pants; it’s defined by what’s inside your brain.” His therapist helped him put his feelings into concrete terms, and she confirmed his self-diagnosis. “I was indeed transgender,” he writes. “Her official diagnosis was critical to me for a few reasons… It validated what I’d known all along and gave me a major sense of relief; I was not crazy. Second, it made my situation very real. This wasn’t going away.” Lastly, it checked off a box in the requirements then for the gender reassignment process, now called gender confirmation surgery.

With the official diagnosis, Edwards was able to start transitioning in 1995. It took years and presented more hurdles as he tried to find a U.S. doctor capable of performing “bottom surgery.” In the book, Edwards describes a hilarious, cringe-worthy meeting with a surgeon in which he and his parents are shown photos of different penises and are then asked to “pick the ‘imposter’ out of a lineup.”

The process to change sexes is “not a one-and-done deal,” Edwards emphasized. From 2002 to 2007, he underwent surgery 22 times. “It’s an expensive, painful, and time-consuming proposition with the potential for myriad complications and no guarantees when it comes to aesthetics or sensation,” he said, noting that the challenges prevent many transgender men from pursuing it. “I felt like I was in what would have been Dante’s tenth circle of hell. But I’d do it all over again if I had to. The feeling of finally being complete — of being who you really are — trumps everything.”

By writing about the surgeries in a forthright, conversational way, Edwards hopes to diminish the stigma around the subject. “By not talking about it, it makes it feel like it’s shameful to have surgery, and it’s not,” he said. “And, frankly, it’s what everyone really wants to know about. So if we want people to focus on the bigger issues like trans rights and violence against trans people, let’s just get the information out there so people can get over it and we can all move on.”

Edwards started writing BALLS in 2012, and it took four years to get it published. “That’s almost as long as it took to make my penis,” he joked, “and at times it was a lot more painful.”

But, “I wanted to write a book that would help change perceptions and give people a more accurate picture — that there are all kinds of transgender people,” he said. The culture is beginning to shift toward acceptance, but trans people, he explained, have typically been portrayed as deviants or freaks. And even Caitlyn Jenner, who transitioned in the public eye, is not relatable because she’s a celebrity, Edwards added.

“I felt like I was in what would have been Dante’s tenth circle of hell. But I’d do it all over again if I had to. The feeling of finally being complete — of being who you really are — trumps everything.”

In telling his story, Edwards’s goal is twofold: he hopes to educate, and to serve as an example of a regular guy who successfully transitioned. “Thankfully, my story has a happy ending,” he writes. “But I’m one of the lucky ones.”

While promoting and talking about the book, he’s heard from parents of trans teens who appreciate the message that their children can live a fulfilling life. “If they can envision that, they’re more likely to be supportive,” Edwards said. “And if the child who is trans can envision that, they’re less likely to try to kill themselves.”

Edwards is donating a portion of the book proceeds to a scholarship fund at Camp Aranu’tiq, a summer camp in New Hampshire “where [transgender] kids can meet people who are like them and not worry about being bullied or what bathroom to use, they can wear whatever they want, and just have peace,” he said. His family donated money to help the camp purchase a permanent place last year; previously, they were renting space from other camps. On Sundays in the main dining room — named Edwards Hall — they serve chicken and pilaf, “because that was my family’s tradition, and I came out to my family during one of those dinners,” he said.

Check out BALLS for a complete picture of Edwards’s transition and more of his lively tales — being upstaged by a backyard mole while coming out to his family, informing his company’s stakeholders in “the board-doom,” dating a member of the Nashville bikini team, and (a significant rite of passage) learning how to pee standing up.

Pictured here, the 1991–95 Colgate women’s rugby team reunited in Chicago in 2014. While Edwards was going through his transition, he attended the wedding of one former teammate. He tells the story of that experience in a chapter of his memoir, Balls, called “Please Allow Me to Reintroduce Myself.” An excerpt follows.

My newfound confidence would soon be tested at the wedding of one of my former college rugby teammates. Despite what you might picture, the Colgate women’s rugby team was not a bunch of big, burly lesbians. The women came in all different shapes, sizes, and degrees of hotness. Some were gay, some were straight, and come to find out, one of us was even a guy! But we all shared in camaraderie and tradition…

Most players were called either by their last name (e.g., Price, Fedin) or a nickname given to them by an elder member. There were some classics — Shiner, Hippie, Pinko, Crash, Thud, Skippy — and last but not least, Swede, who was the one getting married and reuniting the gang, most of whom would be seeing me for the first time as a guy. And having gone through a mastectomy and almost two years of testosterone injections, the change in my appearance at this wedding would be dramatic. It might be awkward at first, but they would accept me. I was sure of it … kind of.

I made the two-hour drive alone that Sunday but had planned to meet up with Price and Fedin beforehand to avoid having to walk into the church by myself. Instead, I got lost and missed my window of opportunity. Luckily the testosterone had yet to override the female part of my brain that has no qualms about asking for directions so I made it to the church just in time to see Swede make her grand entrance. As she headed down the aisle, I quietly slipped into the back and scanned the pews for any of my former teammates. No luck. The place was packed and everyone was facing front. The only way I’d be able to ID any of them now would be by the familiar maroon jacket that said “Colgate Rugby” on the back, and I highly doubted any of them would be wearing one of those. Well, maybe Keeler.

I sat in the back row by myself, which made me feel all the more self-conscious until I looked across the aisle and saw a pretty girl smiling at me. It was Thud — or was it Crash? I could never remember who was who, and having not seen either of them in four years only made it more challenging. I smiled back and mouthed, “I got lost.” She mouthed back, “We did, too.” Then Crash (or was it Thud?) leaned in and waved.

Well, the good news was they recognized me. The better news was when we met up at the bar at the reception it was as though we were all back at The Jug, minus the crappy beer and all the pushing and shoving. The fact that I was now a different gender didn’t seem to matter to anyone. Some even considered it an advantage to have a dance partner at the ready. According to Siedsma, our performance to “Dancing Queen” was “epic.” Not sure what everyone else thought of it, but it did catch the eye of one particular girl at the wedding. She was just my type: short, cute, and blonde with glasses that screamed, “I’m smart but I also know how to have fun.” We danced into the night and I’m truly convinced we could’ve had a future together, had she not been 5 years old.