By Rebecca Costello | Photography by Andrew Daddio

“The story of the Earth is told in its rocks, minerals, and fossils. Over many centuries, humans have collected and catalogued a fascinating array of specimens. Some of these are spectacular examples of environments that no person has ever visited, such as the deep interior of the Earth, or of ancient worlds that will never again come to be. We use these specimens to interpret the history and evolution of the Earth and to better understand nature and all its mysteries.”

Thus reads the welcoming banner at the Linsley Geology Museum, one of the gems of the Ho Science Center. Designed by the geology faculty as a teaching museum, one of its main themes is New York State’s geologic past, but it features fossils, gems, minerals, and rocks from all over the world.

“We also wanted to evoke a sense of the beauty and wonderment about all of these objects,” said Di Keller ’81, MA’88, senior lecturer in geology who chaired the museum’s design committee. “These are the sorts of things that get us excited as geologists.”

GEMS

Did you ever wonder where the idea of birthstones came from? Professor Rich April covers that and more in Gems, his Core Scientific Perspectives course.

“We look at the science of gems, how they form, how they get their beautiful color and luster,” he said. “Then we look at their history and how they have meshed with the different cultures of the world. We also talk about their place in current events, such as the U.S. import ban of rubies and jade from Myanmar.”

The birthstone tradition originated with the Old Testament book of Exodus. The high priest, Aaron, wore a breastplate containing 12 gemstones representing the 12 tribes of Israel. Later, gemstones were tied to the signs of the Zodiac; people began to carry around the stones representing the sign they were born under. Over time, some of the months’ stones have changed. Prof. April’s birthstone, for example (March), is aquamarine, but it used to be heliotrope.

Star Sapphire

Stars in ruby and sapphire result from tiny inclusions of rutile needles called “silk.” This beautiful 21-carat blue-gray star sapphire, a relatively old gemstone from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), was given to Colgate in 1980 by Anne Cheryl and Clifford Rathkopf ’66. (Their son Christian ’10 ended up majoring in geology.) Professor Rich April named it the Colgate Star.

MINERALS

Herkimer Diamond

New York State’s Herkimer County (about 30 miles northeast of Colgate) is one of the few places in the world where quartz crystals such as this one can be found. It grew in a cavity in the Little Falls Dolostone that formed from sediments deposited in a highly saline sea approximately 500 million years ago. Crystals typically grow with one end attached to a cavity wall, which would allow only one end of the crystal to form a point. Herkimer diamonds are unique because they have points on both ends, suggesting that they had little or no contact with the surrounding rock as they grew.

Stibnite

FOSSILS

Trilobite

While excavating for the driving range at Seven Oaks back in 2002, local heavy-equipment operator Stub Baker opened up a large cache of fossils. He notified the geology department, and soon professors, students, and local fossil buffs were swarming the area. Baker gave this particular pair of trilobites to longtime geology professor Charlie McClennen, whose wife, Hannah, donated them to Colgate after Charlie died in 2007.

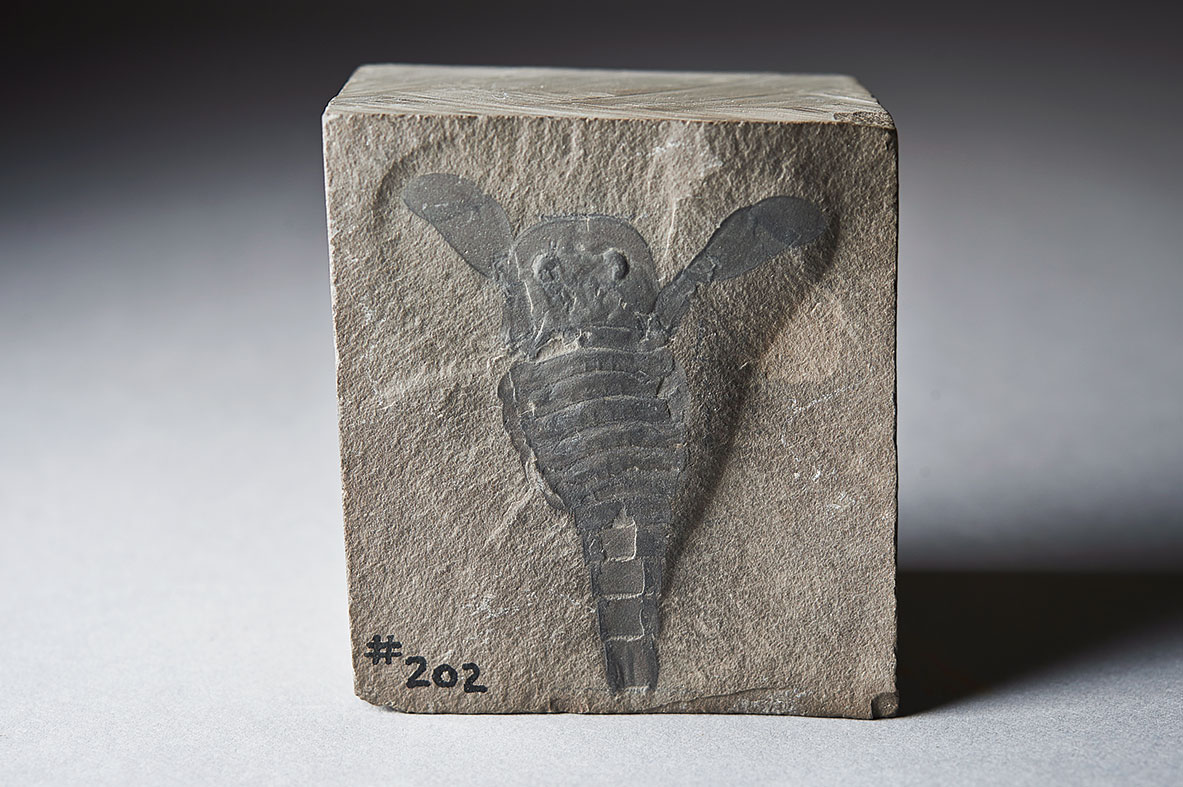

Eurypterid

The New York State Fossil – Although now extinct, eurypterids were the largest of all arthropods (invertebrate animals with jointed exoskeletons). Distantly related to horseshoe crabs, scorpions, and spiders, these formidable predators had grasping appendages, large swimming “paddles,” many legs, and two pairs of eyes. The famous New York eurypterids are found in Silurian rocks not far from Colgate that formed in high-salinity marine environments.

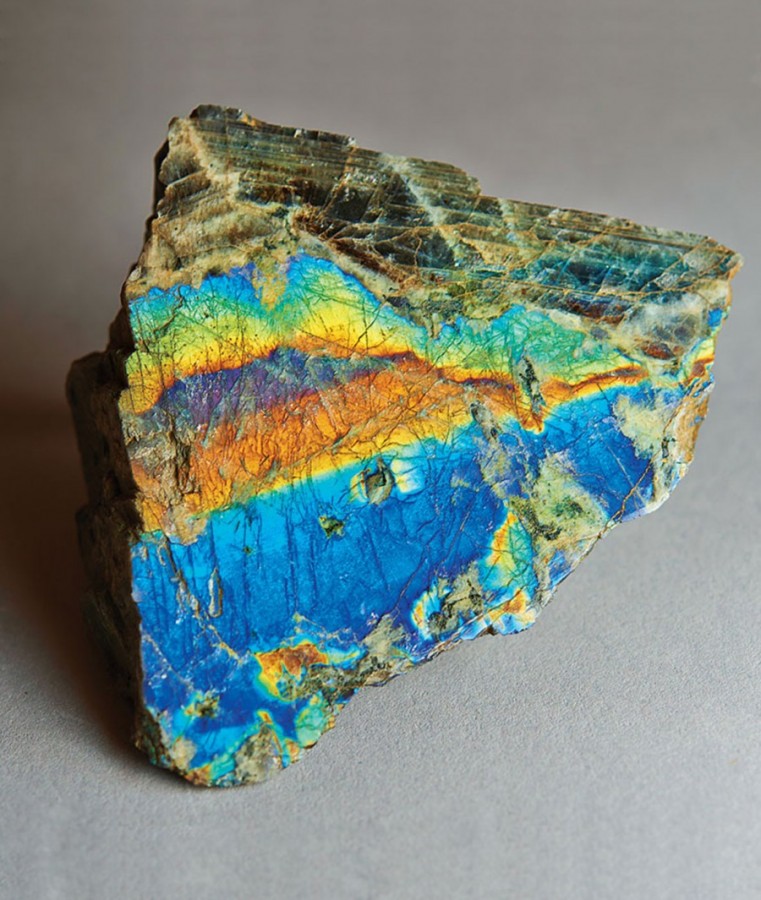

ROCKS

Folded Slate

This slate began as clay-rich sediment deposited offshore on a continental shelf. The sediments lithified into shale, which was then metamorphosed and folded when an island arc (similar to modern-day Japan) collided with the East Coast of North America. This collision thrust the slates up from the continental shelf and moved them inland toward the west, in an event called the Taconic orogeny.

About the Linsley Geology Museum

The Linsley Museum welcomes more than 5,000 people through its doors each year, including students in Colgate classes — from geology, the core, and even art and art history — as well as their families, alumni, admission tour groups, community members, and more than 2,000 local school children.

It’s dedicated to Robert M. Linsley, a beloved geology professor at Colgate from 1955 to 1992. Fondly remembered for his enthusiastic teaching style and penchant for Coca-Cola, Linsley, who died in 2006, specialized in the paleontology of gastropod mollusks (snails). The museum, made possible through the generosity of 61 contributors led by Sylvia and Malcolm Boyce ’54 and Patricia and G. Peter O’Brien ’67, opened in 2009.

A number of features in the museum reflect the university’s people and locale, including specimens and displays that were collected, donated, or created by Colgate professors, students, alumni, or community members. Some examples:

- Fossils from the collection of famed paleontologist G. Arthur Cooper ’24, MS’26, H’53, whose career interest was sparked in the Colgate quarry. Cooper went on to earn some of the most prestigious medals in the sciences (also on display).

- A display of skulls illustrating the mass extinction of large-bodied animals 12,000 years ago, designed by Linsley’s son David Linsley, a paleontologist who works for the geology department.

- Colgate’s most famous artifact — the Oviraptor philoceratops egg that, when discovered in Mongolia in 1923, was the first direct evidence of dinosaur reproduction.

- A mastodon tooth found near the playground at Hamilton Central School in the 1970s by a young boy who sold it to Colgate for around $15.

- Rotating “time column” — a favorite of visiting schoolchildren, and a nod to the original two-story column in the Lathrop Hall stairwell.

“When I look around here, I don’t see just the displays. I see everybody who made this museum possible,” said Di Keller.

If you go:

Mon–Fri: 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Special evening and weekend hours for campus events like Family Weekend, graduation, and Reunion.

Objects not shown to scale. Many descriptions in this article were drawn from the museum’s labels.