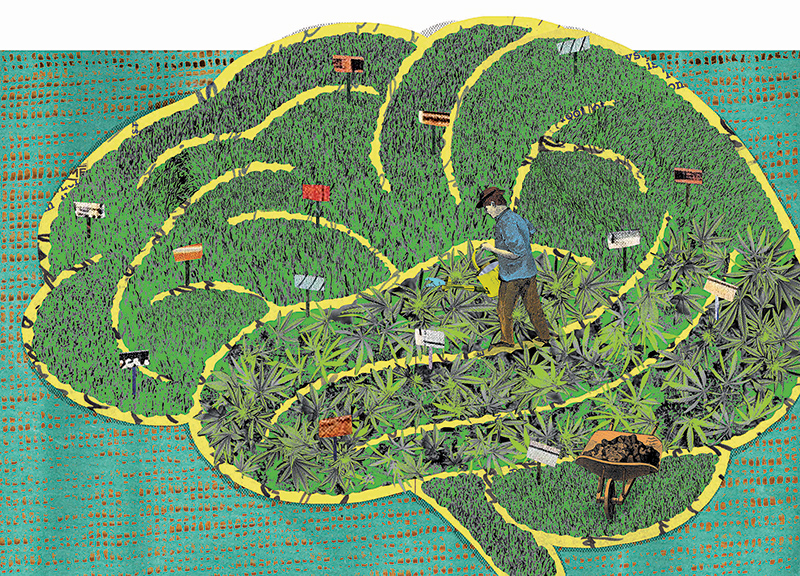

Illustrations by Oliver Weiss

The growing cannabis business has created entrepreneurial opportunities for some alumni, while others address the potential consequences.

Up until a couple of years ago, Ernie and Callie (Rice) Craumer, both Class of ’77, were leading suburban lives in Greenwich, Conn. Ernie worked in finance, and Callie ran her flower shop when she wasn’t shuttling the kids between schools and sports. Fast forward to 2019 and things have changed: the Craumers and their daughter Caitlin ’05 now live in Colorado, where they sell marijuana from a pair of cannabis dispensaries.

Their store in Niwot, an affluent community near Boulder, has an astonishing number of products. There are, of course, several strains of marijuana buds and the usual accessories. But there is also an array of edibles and other cannabis-infused products: 15 types of gummies, 78 vaping cartridges, a dozen drinks, 24 different mints and hard candies, 15 topicals (salves, bath oils, soaps, and massage oils), and 32 kinds of chocolate.

“If someone predicted that I would end up selling weed, I would have called them crazy,” says Caitlin, who captained Colgate’s swim team and previously worked at an advertising agency in Manhattan.

The other surprise is the customers. Yes, there are some young men and women who could be described as “stoners,” but they’re the exceptions. The Craumers say the average age of their customers is 48. “They don’t come here because they want to get messed up,” Callie says. “They come because they want to take the edge off, to feel better, or to do something about pain, sleeping, stress, or anxiety.”

Whether you think the legalization of marijuana is a godsend or an epic disaster in the making, it’s a movement that’s taken on tremendous, possibly unstoppable, momentum now that 10 states permit its recreational use. Legalization has also set off a frenzy of entrepreneurship — and Colgate alumni are playing an outsized role.

Some of the Craumers’ best-selling chocolates are made by a company called 1906, which was founded by Peter Barsoom ’92. After spending 20 years working for several financial services companies, he decided to set out on his own in 2014. Barsoom thought about ventures involved in health care and cryptocurrency but settled on legalized cannabis because of its growth potential. “Going from prohibition to regulated markets is a historic opportunity,” he says. Barsoom named his company for the year when a federal law was enacted that ushered in the era of cannabis prohibition.

Barsoom’s specific strategy is centered on solving what he believes to be the three biggest problems with most edibles: “They taste terrible, you don’t know how they’re going to make you feel, and you don’t know when they’re going to make you feel that way.” By selecting particular strains of marijuana as well as other plants (some of them herbs used in Chinese medicines) for each of his products, Barsoom says, all of them are fast acting and each one has a singular benefit: “Midnight” helps people sleep, “Go” enhances energy, “Love” leads to sexual arousal, “Chill” promotes relaxation, and “Bliss” just makes you happy. A box of six chocolates costs $24 — more than most edibles, but Barsoom says that’s not a problem because his main target markets are women and seniors. “We see our competition as being a bottle of wine,” he says.

Barsoom has raised $16 million in investment capital, and 1906 has become one of Colorado’s fastest growing edibles companies. He’s now working to expand into several other states and broaden his product line to include beverages, baked goods, and tablets. “Over the next five to ten years, there are going to be billion-dollar brands in the cannabis industry,” he says, “and we expect to be one of them.”

More than 80 percent of 1906’s sales take place by way of LeafLink, an online marketplace founded by Ryan G. Smith ’13 that sells 44,000 different cannabis products to more than 3,000 retailers. The Craumers buy a substantial majority of their products through the company. “I don’t know how we could operate without LeafLink,” says Callie, who didn’t know about the firm’s Colgate connection until she was interviewed for this article. With 62 employees, LeafLink facilitates more than $1 billion in transactions on an annualized basis — about 16 percent of legal wholesale cannabis transactions nationwide.

Smith’s entrepreneurial career began early. Growing up in Manhattan, he used eBay to sell everything from preowned cell phones and ski clothes to, on one occasion, a single sneaker. If his parents couldn’t find something at home, they assumed Ryan had sold it. As a first-year at Colgate, he joined Thought Into Action (TIA), the alumni-led incubator program that coaches student entrepreneurs, and he founded several ventures, starting with one that sold eco-friendly paper made from tropical plants. He also launched a real estate information service, which he continued to run after graduation. After Smith sold the business in 2014, he was in the market for a new idea.

LeafLink came together after Wills Hapworth ’07, a founder of TIA who now works as its alumni executive director, introduced Smith to Zach Silverman, another young entrepreneur who had recently sold a company. When Smith and Silverman met for coffee at Grand Central Station, they spoke in the shorthand that’s commonplace among the city’s bustling community of young entrepreneurs. “I want to do a marketplace for an industry that’s totally underserved,” Smith said. It was clear to Silverman that Smith was talking about a web-based system for facilitating business-to-business transactions. When Silverman suggested a marketplace for cannabis, Smith pounded a fist on the table and declared, “That’s perfect.”

With Smith as CEO and Silverman in charge of technology, they formed a company and started spending time in Colorado, where recreational use had recently been legalized. Business dealings between dispensaries and their suppliers were even more inefficient than the partners had imagined, mostly conducted via phone calls and texts. “When we asked if they’d like to have a simple way to do business,” Smith says, “they reacted enthusiastically.”

LeafLink is based in Lower Manhattan and Los Angeles, where employees sit in open spaces, at long tables with large monitors. The offices are usually as quiet as a library because of the work involved with building and maintaining the company’s website. A display case in the Manhattan office contains a selection of cannabis products, but all of the boxes are empty because none of them are legal in New York. In fact, marijuana itself does not play a role in LeafLink’s office culture. Smith says it’s not a cannabis company as much as it’s a technology company and that employees are no more likely to consume marijuana than those at other tech firms.

LeafLink has raised $14 million from investors and has expanded into new states as quickly as they legalize. The legal patchwork is a mixed blessing. Because products can’t be shipped across state lines, the Craumers can only buy and sell Colorado-created products, Barsoom needs to set up a manufacturing facility in each of the states where he sells 1906 products, and LeafLink can’t function as a single marketplace. On the other hand, the extra burdens have hindered tobacco and liquor companies and other large firms from entering cannabis businesses. But Smith says it’s only a matter of time before major players jump into every corner of the industry, including LeafLink’s, so he says he’s in an all-consuming race. “The industry is growing fast, but we have to grow even faster to make sure our market penetration grows.”

Blunt Truths

Of course, not everyone believes a rapidly expanding cannabis industry — or legalization itself — is a good idea. Colgate’s Charles A. Dana Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience Scott Kraly, who studies how psychiatric medications and recreational drugs affect human behavior and the brain, is among the skeptics. He says legalization should not have been even considered without far more research into the risks of cannabis use.

“Legalization is happening because of a change in attitudes, not science,” Kraly says. “People are saying, we’ve legalized alcohol even though we know it’s harmful, and tobacco is legal even though we know it’s harmful. Marijuana isn’t as harmful as either of them, so why not? Let’s go with it.”

Kraly says marijuana is relatively safe in terms of addictiveness and that it may well have altogether less significant dangers than either alcohol or tobacco but, he says, it was a mistake to base legalization on impressions of relative risks. And while there has been surprisingly little research on the medical impacts of recreational marijuana, he says, some risks are known. “People pooh pooh the notion that pot is a gateway drug, but there is some evidence that it actually does play that role,” Kraly says. “Say a fifteen-year-old tries pot and he likes it. If he gets away with it, he’s going to be more willing to take further risks” with more dangerous substances. The impact on adolescents is a particular concern because legalization will inevitably increase their access to marijuana, especially edibles, and research shows that significant cannabis use can permanently damage still-developing brains. “What’s happening in Colorado is a grand social experiment,” Kraly says. “What ends up happening there will tell us whether legalization was a good idea or a bad one.”

In addition to potential health risks, there are other dangers to consider. A Colgate alumnus who is a police officer in a state where recreational marijuana is allowed says the evidence is already mounting — starting with dangerous driving. “People are getting into their cars after smoking pot and driving their kids to preschool, and they think that’s OK,” he says. In fact, driving while impaired is illegal, but enforcement is difficult. “We don’t have a breathalyzer for pot,” the officer says.

A policeman for almost 20 years, this alumnus declined to be named. “I work for a police department in an incredibly liberal city,” he explains, adding that he could lose his job for sharing his views about legalization. That reflects another problem, he says: There’s been such a rush to legalize that voters and legislators haven’t paid enough attention to voices like his. As a result, he says, there is insufficient appreciation for how legalization constrains law enforcement. “I can’t tell you how many times a marijuana investigation led to the detection of other crimes —burglaries, firearm violations, and major drug dealings. So now we have one less tool.” Like Kraly, this alumnus says legalization has come far too quickly: “We jumped into the deep end with all our clothes on when we should have tried putting a toe in first.”

Debbie Rush ’86 has also considered the ramifications of changing cannabis laws. For the last 30 years, she’s been working in the Bronx as a lawyer for the Legal Aid Society, the nation’s largest provider of legal services to indigent defendants. She says the aggressive policing and mandatory sentencing laws that resulted from the “War on Drugs” have had a catastrophic impact, particularly on minority groups.

“Marijuana laws have had a hugely disproportionate impact on blacks and Hispanics because they are arrested at much higher rates,” she says. “If you’re a white male smoking pot in Central Park, you’re not going to be arrested. If you’re a black guy in the Bronx, there’s a good chance that you’ll end up in handcuffs.”

At every stage, she says, people of color have been dealt with more harshly. In addition to being searched and arrested more frequently, they are more likely to be sent to prison, and their sentences are longer. And for anyone who has been found guilty of marijuana possession, the collateral damage can be profound. “Since marijuana is a drug under federal law, you have a drug offense,” she notes. “That makes it difficult to get a job, and if you want to go to college, you can’t get federal student loan money. For someone to be unable to go to college because they’ve had a single joint is insane, but that’s the law.” In recent years, the New York Police Department has changed its approach. First-time offenders are generally not prosecuted. But Rush says a second offense can still lead to a criminal record.

The Complications of Legalization

Andrew Livingston ’12 has been pushing for legalization since he joined the Colgate chapter of Students for Sensible Drug Policy his first year. At the end of his sophomore year, he told his parents that he hoped to turn the campaign for legalization into a career. And he has. Immediately after graduation, he became a full-time activist in Colorado, where voters approved legalization a few months later. He then became the director of economics and research at a new law firm, Vicente Sederberg, which is entirely devoted to serving clients involved with cannabis.

Today, the firm has 75 employees. Its office just outside of downtown Denver mostly looks like that of other mid-sized law firms, but there are some obvious differences: almost no one is over the age of 45, and you can find marijuana-inspired artwork in many of the offices.

Livingston, who is not a lawyer, assists lobbying groups that are working to influence how laws and regulations are written in states considering legalization. For commercial clients, he develops financial projections showing how various cannabis markets are likely to develop. The legal part of the industry, $8–10 billion today, will grow to $40–60 billion in the next six years, he predicts. He believes the illegal trade, which he estimates at $30 billion, will eventually disappear. “People aren’t going to do business with illicit dealers when they can go to a store where they are more likely to get quality products,” he reasons. (The police officer disagrees, noting that the taxes imposed on legal marijuana give black-market pot a substantial price advantage.)

Livingston, who is not a lawyer, assists lobbying groups that are working to influence how laws and regulations are written in states considering legalization. For commercial clients, he develops financial projections showing how various cannabis markets are likely to develop. The legal part of the industry, $8–10 billion today, will grow to $40–60 billion in the next six years, he predicts. He believes the illegal trade, which he estimates at $30 billion, will eventually disappear. “People aren’t going to do business with illicit dealers when they can go to a store where they are more likely to get quality products,” he reasons. (The police officer disagrees, noting that the taxes imposed on legal marijuana give black-market pot a substantial price advantage.)

While Livingston is pleased by the move toward legalization, he isn’t completely satisfied. Why, he asks, are there bars for consumers of alcohol but nothing similar for pot users? Answering his own question, he points out that while most of the legislators who legalized alcohol after Prohibition did, or wanted to, drink, pot legislation has been mostly written by nonusers. “Sixty percent of Americans are in favor of legalizing cannabis, but only ten percent are users,” he says. And because lawmakers are motivated less by enhancing user happiness than the pursuit of tax revenue, no one is talking about creating pub-like options for marijuana consumption. As a result, he says, “The culture of cannabis use hasn’t really changed. It’s no longer underground, but it’s not really above ground either.”

Laws are also complicated by the division between marijuana and hemp. Marijuana contains tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is what causes psychotic highs. Hemp contains cannabidiol (CBD), which does not have a psychoactive effect, but is said to alleviate pain, insomnia, anxiety, and depression, among other problems. Although there is little scientific research to support any of the claimed benefits, CBD products are proliferating. The legality of CBD is also murky. Unlike products that have THC, those with CBD are now permitted under federal law, but they are still restricted by some states and municipalities.

Jonathan and Leah (Werner) Schultz, both Class of ’96, are developing CBD-infused soft drinks. After Colgate, they spent 14 years living in Cleveland where Jonathan worked for a bank before the couple started a small software company. Because they could run that business from anywhere, they moved to Denver in 2012. Two years later, they purchased Backyard Soda, a producer of carbonated drinks that were sold only in Denver. With Jonathan responsible for product management and production, and Leah handling the bookkeeping and social media, Backyard Soda products are now sold in more than 100 retail locations throughout Colorado and in several other states.

Now they’re working to create CBD-infused sodas with three flavors that are designed, in part, to overcome the “hempy” taste that is characteristic of CBD extracts: ginger lime, mango jalapeno, and pomegranate orange blossom. “I think infusing soda with CBD is a potentially huge opportunity,” Jonathan says.

As it happens, Jonathan’s Colgate roommate, Reed Lewis ’96, is already making CBD products. Lewis moved to Snowmass, Colo., shortly after graduation. Thanks to the Colgate sweatshirt he frequently wore, he met Dick Kelley ’68, the owner of a popular liquor store, and after working in the store for a few years, Lewis ended up buying it. He later added a specialty food shop, and that’s where he sells his own creations: CBD-infused teas and chocolates.

All of Colgate’s cannabis entrepreneurs are eager to expand, but the Craumers warn that their industry is more difficult than it may appear, in part because of challenges unique to the industry. For example, after they bought a building in Niwot’s main retail district in 2014, it took a stressful three years to secure the permits they needed to operate a dispensary. More than 1,000 letters were written in opposition. While a substantial majority of Coloradoans are in favor of legalization, the Craumers learned that no one wants the commercial consequences to be located nearby. Once the dispensary opened in 2017, marketing efforts were complicated by regulations that allow advertising only in publications that can be shown to have predominately adult readerships.

Their pair of dispensaries now has more than $5 million in annual sales, and they’re profitable. Within a few years, the Craumers hope to add at least three more dispensaries. But they, too, have reservations about cannabis use, at least when it comes to themselves. None of them is a regular user. “I tried it in high school and college, but I didn’t like it that much,” says Callie. “I still don’t. I prefer chardonnay.”

G. Bruce Knecht ’80 is a former senior writer and foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal. Author of The Proving Ground: The Inside Story of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart Race and Hooked: Pirates, Poaching and the Perfect Fish, he has also written for the Atlantic Monthly, the New York Times Magazine, and Condé Nast Traveler. He lives in New York City.