A sampling of scholarship being explored by professors and their students

Cracking the Kailasanatha Code

One of southern India’s most cherished temples has a secret that’s been buried since the 9th century. Professor Padma Kaimal believes she’s figured it out.

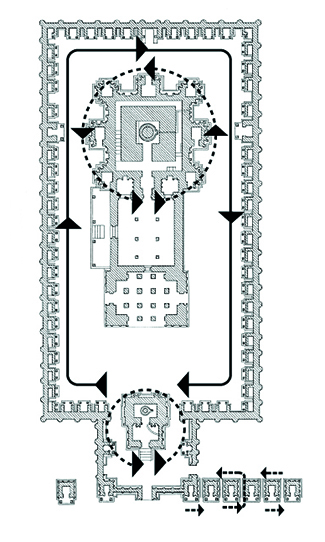

For centuries, visitors of the Kailasanatha temple in Kanchipuram, India, have entered the inner courtyard and followed its path lined with sandstone-carved deities including Shiva, Parvathi, and Skanda.

Hindus believe it is most auspicious to circumambulate temples by moving clockwise. But by studying clues laid out in a counterclockwise direction through Kailasanatha, Professor Padma Kaimal discovered a secret meaning — one that hasn’t been affirmed since the 9th century.

“After thinking about it for a few decades, I finally figured it out,” says Kaimal, who has written about the temple in a forthcoming book from University of Washington Press. “It’s a puzzle, and all the pieces fit together.”

“After thinking about it for a few decades, I finally figured it out,” says Kaimal, who has written about the temple in a forthcoming book from University of Washington Press. “It’s a puzzle, and all the pieces fit together.”

The Kailasanatha monument was built by Rajasimha, ruler of the Pallava Dynasty, in the late 7th to early 8th century. Kaimal, an art and art history professor, first visited in 1984. “I was overwhelmed by it, and I took all the pictures I could,” she recalls. “I just kept returning again and again.”

Surrounded by a high enclosure wall with menacing stone lions, the complex includes a central shrine and 58 subshrines. The more Kaimal visited, the more photos and notes she took, mapping out diagrams, finding patterns, and uncovering layers of significance.

On the north side of the central shrine, the sculptures represent discipline: Rigid bodies engage in themes of battle, conquest, domination. The figures on the south side of the building show continuity: Languid bodies display nature, sexuality, rebirth. “These modes of being were both important to the royal family,” Kaimal says.

The sculptures, she soon realized, also appear to be moving in two directions — some guiding visitors clockwise and others leading visitors counterclockwise.

The inscriptions on the buildings, too, are carved both clockwise and counterclockwise. One, in particular, puzzled the professor: a 12-verse poem that reads counterclockwise and runs below statues of Shiva and the goddesses. It has been believed, until now, that the sculptures and the inscription below tell two unrelated stories.

The courtly poem carved around the building praises King Rajasimha, narrating his descent from gods, sages, and valiant kings, and tells of his great deeds. The sculptures, meanwhile, depict the gods fighting against evil, ruling from their thrones, dancing, flirting, and marrying.

“Even though they seem to be about different things, they’re sharing ideas,” Kaimal says.

Working with a colleague to carefully line up the ancient Sanskrit words with the statues above, Kaimal spent months poring over it and eventually cracked the code. “Suddenly my hair was standing on end as I thought, oh my god, it’s coming together, it actually means something,” she says.

The sculptures and the inscription “are in dialogue with each other to tell a third story neither medium could tell on its own,” Kaimal explains. “The secret message that comes at the end of the two stories is that the king is continuing the work of the gods, returning the world to a utopia, and fusing with the god [Shiva].” Furthermore, the inscription states that King Rajasimha took initiation into a tantric sect, indicating that he was renouncing this life in order to join with the divine.

In the Hindu faith, circumambulating counterclockwise is done in the hopes of attaining transcendence and escaping rebirth, while most people move clockwise in order to achieve a prosperous life on earth. So only those who moved counterclockwise through Kailasanatha would have known the secret meaning. Those people were the esoteric sect initiates, believed to be the Pallava kings.

“For the king to take initiation into a secret sect was a pretty big deal,” Kaimal says, explaining that sects are for people who are leaving society — a counterintuitive goal for kings. But, she believes, Rajasimha wanted the best of both worlds.

The king sought different kinds of power: magical strength on the battlefield, the potential to nurture and transform the whole world, and the ability to unite with god. The symbolism throughout the temple represents the king’s desire to simultaneously continue his lineage and “let go of life and seek transcendence,” Kaimal says. “These are not polarities, these are complementary. He wanted both.”

In a way, the Pallava kings did attain both. Although their dynasty died in the 9th century, their legacy lives on through the Kailasanatha temple — a monument that attracts flocks of tourists and devotees alike.

As the first person to read the temple this way, Kaimal is relieved that her thesis has been accepted by some scholars around the world. “A lot of people feel possessive about this monument,” she says. “It’s kind of like the Sistine Chapel.” Still, despite their acceptance, some of Kaimal’s Hindu colleagues took precautions after her presentation at the temple: To undo the energy of going counterclockwise, they took several clockwise trips.

Book Smarts

When working on her forthcoming book on the Kailasanatha monument, Professor Padma Kaimal recruited students to help. Hannah Bjornson ’15, an art and art history major, conducted research for the chapter about the physical changes to the temple over the centuries.

“She was turning up archeological reports from the British Library — stuff I would never have known how to find,” Kaimal says. “She spent the summer sending me these goldmines.”

Three other students also lent their expertise. Shan Wu ’15, Daniel Berry ’17, and Angel Trazo ’17 produced diagrams to complement Kaimal’s text — a hefty job considering the numerous sculptures, inscriptions, and symbols.

The students’ work, Kaimal says, allowed her “to tell the story more clearly.”

— Aleta Mayne

Welcome to 1940

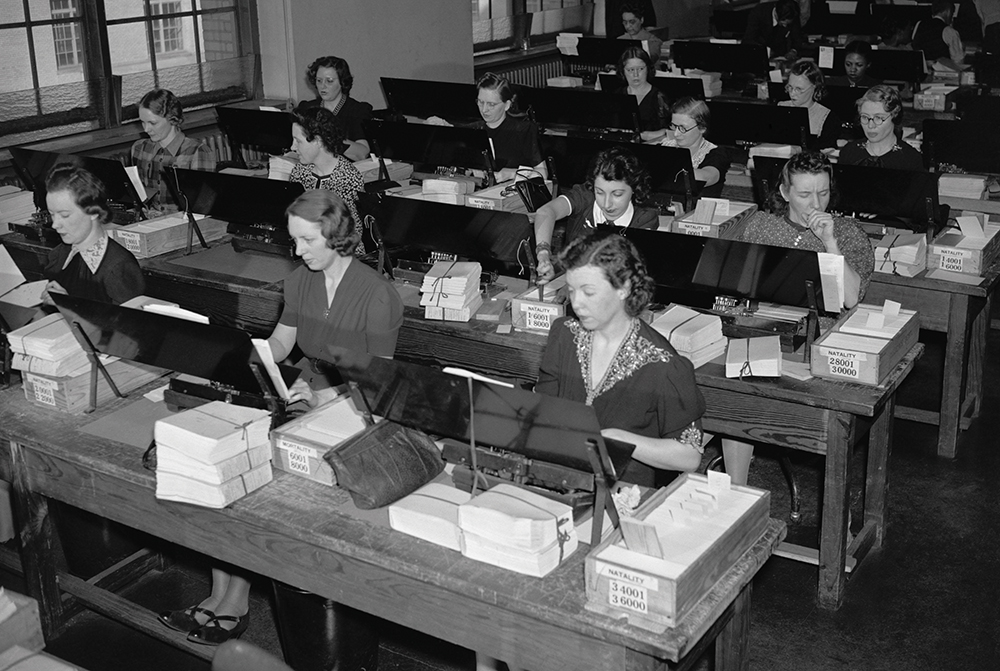

Live people were reduced to data. Professor Dan Bouk is bringing them back to life.

Knock. Knock. Knock.

Earnest Forning answers the door. He’s a janitor in 87 Hamilton Place, the Harlem apartment building where he lives. He’s face-to-face with enumerator Lucile Kenn, who asks him his age (51), heritage (German), income, and other personal details. Kenn records them in her ledger, which would become an entry in the 1940 United States Census.

More than 75 years later, Dan Bouk is standing on the sidewalk, looking up at 87 Hamilton Place, retracing Kenn’s steps.

Through archival documents and the 1940 census, Bouk, an associate history professor, is rebuilding the stories of mid-century Americans for his book, The Inventory of Democracy: The 1940 Census and the Politics of Facts, the release of which will closely follow the 2020 census. From the Minnesota garbageman who told the census taker he earned no wages because he didn’t want the government to know his income to poet Langston Hughes, whose roommate answered the enumerator’s questions for him, Bouk uses data to reconstruct lives, one by one.

“These recreations fascinate me not only for the stories they tell about those being enumerated,” Bouk writes on his website, “but [also] because they invite us to learn more about the enumerator, one of the too-often faceless thousands mobilized to record for the nation and for posterity the facts of every American life.”

Stories like Kenn’s drive the narrative on Bouk’s website, censusstories.us, the precursor to his book. Providing a view into 1940s America, he uses information from the National Archives, local history collections, news stories, and articles from secondary literature to give the census a narrative and make his research more relatable. Bouk’s research brings to light the realization that the names listed in the census aren’t just numbers on a vintage spreadsheet — they’re people, with compelling stories and backgrounds, who deserve to be remembered.

Bouk, who has a degree in computational mathematics and built his site from scratch, is no stranger to sifting through data the layperson would find snooze-worthy.

“I’m interested in things shrouded by cloaks of boringness. They look boring because they’re important,” Bouk says. “The census count matters a lot in the day-to-day administration of government, so it matters in our lives.”

The 1940 census came when President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was in full swing, signaling a transition in the way the government thought about its economic responsibilities. For the first time, the census asked questions about income and housing that would be used to develop the new welfare state. With the 2020 census looming, these principles are largely still in place today.

“The census is a part of the mechanism by which the United States federal government is allocating resources and by which it makes decisions about how

to shape the economic lives of people,” Bouk says.

Through Colgate’s first history lab (which he started), Bouk tasks students with exploring areas of the census he wouldn’t be able to on his own. This fall, the students, Andrea De Hoyos ’20, Emily Karavitch ’21, and Ethan So ’21, analyzed the 1940s documents — including a list of census supervisors — searching for anything they deemed interesting. They built a database of their findings, which Bouk uses to aid in further research.

“Normally, I would probably just look at it and say ‘that’s interesting, but there’s nothing I can do with it,’ Because I’ve got this lab, I say, ‘let’s dig into this thing and see what happens,’” Bouk says.

Now, with documents detailing the process by which census supervisors were chosen, the team is matching names from their database to piece together a background for those who changed history by compiling the census. This information will be used in Bouk’s book.

Standing outside 87 Hamilton Place, Bouk thinks back on the meeting between Forning and Kenn. Thanks to the 1940 census, we know more about people like Forning: their ages, jobs, incomes, addresses. Thanks to Bouk and his students, we know their stories.

— Rebecca Docter

Where There’s Smoke

Chemistry professor Anne Perring and Brady Mediavilla ’20 investigate the harmful effects of Western U.S. wildfires.

The devastating wildfires that roared across California in 2018 killed at least 91 people and caused more than $400 billion in economic damage. The most visible consequence of the fires, however, was the smoke that lingered in thick yellow clouds over San Francisco in November and harmed air quality as far east as New York City.

“You can have a fire in California that makes people unable to go out and exercise in Colorado,” says Anne Perring, an assistant chemistry professor.

Beyond the short-term health effects, scientists have a lot to learn about the smoke’s environmental effects on the climate. “Fires are major sources for particles in the atmosphere on a global scale,” Perring says, “but the chemistry can be very different depending on the kind of wood or other fuel that’s burning.”

This summer, Perring and Brady Mediavilla ’20 are taking part in a massive government research project to better understand that chemistry. They’ll be in a NASA plane flying straight into fire plumes in order to measure their composition. The project is part of FIREX-AQ, a joint project of NASA, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), and approximately 40 participating institutions to better understand the effects of fire on global processes, including climate change.

Climate change has increased drought, leading to more wildfires, which in turn can create particles that cause more climate change. Perring and Mediavilla are investigating black carbon, otherwise known as soot, which can absorb solar radiation and lead to atmospheric warming. “By some calculations, it’s the second-biggest forcer of climate change after CO2,” says Perring, who joined Colgate last year after working with NOAA in Colorado. Unlike long-term greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane, however, black carbon only stays in the atmosphere a short time — typically days or weeks.

Former President Barack Obama honored Professor Anne Perring as a recipient of the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers in January 2017.

For that reason, accurately measuring properties of black carbon in fire plumes — including where the plumes are in the atmosphere and how long they last — is crucial to developing climate change models.

For their experiments, Perring and Mediavilla will take turns riding on an old Alitalia DC-8 jetliner, fitted out with a variety of scientific equipment. “The airplane looks ridiculous because there are all sorts of things hanging off of it,” she says. They will use a single particle soot photometer that sucks in particles and vaporizes them with a laser to tell how many are in the air. In addition, it can tell whether they are coated with other organic “goo” that change how they absorb light.

“It should give us a better understanding of the properties of these particles that will be indicative of how they affect the environment,” Mediavilla says. He contacted Perring last summer, looking for research experience in environmental chemistry and sustainability, and he jumped at the chance to be involved in this project. “It’s not something you get the opportunity to do all the time,” he says.

The pair will spend three to four weeks in Idaho next summer chasing wildfires, hoping to take measurements in the air every second or third day.

When they are not flying, they’ll be in airplane hangars using high-powered computer software to crunch enormous datasets. “We have millions of particles every flight to work with,” Perring says. “You can spend a year or two on this kind of data analysis.”

In addition to her work on wildfires, Perring is also pursuing a project with other Colgate students examining the effects of pollens and spores in the air that can cause allergies. For his part, Mediavilla is planning to make the wildfire research the focus of his senior thesis next year, hoping to make a difference on a pressing environmental hazard. “Especially with the increase in burning from wildfires, the more we can look at this, the faster we can incorporate it into climate models,” he says. “Hopefully we can get around to mitigating it before it gets out of hand.”

— Michael Blanding

Virtually Inspired

Colgate scholars are developing an educational experience that encourages young scientists to embrace the pace of academic research

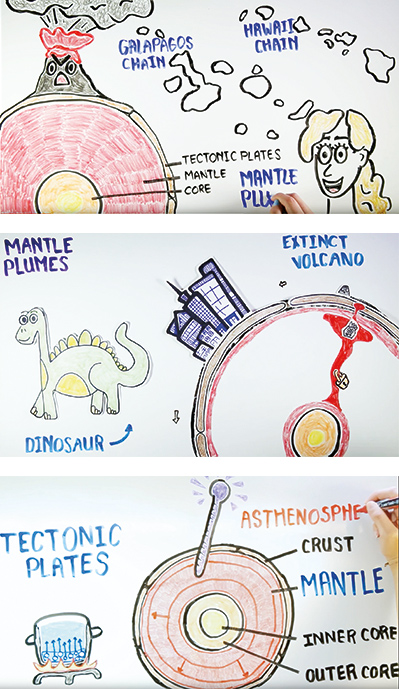

“An expedition on this sort of scale has never been attempted in the Galapagos before…”

So said the promos for the BBC documentary Mission Galapagos (2017). On the program, scientists from across disciplines traveled to the famous archipelago to study its ecology. Volcanologist and Colgate geology professor Karen Harpp went along to search for an island that is rumored to be lost in that neighborhood of the Pacific.

While the scale of the documentary was grand, its scope was limited: In order to meet the demands of TV, BBC producers told Harpp that she would have to find her island during a single five-hour submarine dive. She explained that it was an unlikely outcome — and she was right.

“We didn’t have a homerun answer, and my piece didn’t make it in,” Harpp says. She was frustrated by the message that the documentary, with its quick, cut-and-dried segments, was sending to budding scientists. “We don’t want to deliver science as a done deal, because how is a kid supposed to be inspired to do science when you say, ‘And that’s the answer!’?”

Harpp decided to channel her frustration into the creation of an interdisciplinary academic experience based on the science of the Galapagos. Ideally, this resource could even be used to educate young Ecuadorians about the remarkable resource sitting just off their coast.

Within a year, Harpp was back on the islands with a Colgate team that included Emily Weaver ’20, Caio Rodrigues Faria Brighenti ’20, and Ho-Tung Visualization Lab Director Joe Eakin. For 10 days, the crew collected 3D footage for a project they called Virtual Galapagos.

Upon their return to campus, Brighenti, a virtual reality (VR) developer working in Eakin’s Vis Lab, started stitching thousands of video files into an interactive tour. Weaver began drafting lesson plans to guide the narrative. By the end of the summer, Brighenti had produced … a 15-second experience. Given the render time of VR files and the download time for users, Brighenti says, “drastic change was needed if we wanted to complete anything.”

They also needed to figure out how to deliver their experience to students around the world. Earlier that year, Lev Horodyskyj, curriculum designer at Arizona State University Online, visited campus. He talked about teaching geology in remote locations using an ASU-developed system called SolarSPELL: Solar Powered Educational Learning Library. Designers attach MicroSD chips full of educational media to Raspberry Pi computer CPUs and make the library accessible via mobile phone. No Internet required. Harpp and her team remembered this presentation and thought SolarSPELL could provide a perfect solution to their predicament. They were convinced after further conversations with Horodyskyj and his ASU colleagues.

Drawing in an audience: The Virtual Galapagos team explains concepts like mantle plumes and the motion of tectonic plates through colorful, engaging animation.

Summer two of the Virtual Galapagos project was a churn of activity. The team, including new members Julia Rose Dottinger ’18, Marie Pugliese ’20, formed curricular modules based on topics like mantle formation and animals’ use of currents for inter-island transportation. Pugliese took on the latter. She drew on her experience coordinating educational programs at her local aquarium, scholarly research, and interviews with Colgate faculty members such as geology professor Amy Leventer.

“We knew we needed something that would tie everything together — the children who were going to do this needed a reason to do it,” Pugliese says. So they created characters to draw students into the program: Carlos the blue-footed booby and Adrianna, a Galapagos penguin. Users join Carlos and Adrianna as they travel around the islands, learning interdisciplinary science while searching for elusive pink iguanas.

Dottinger drew the characters (voiced by Harpp’s family members) and whiteboard animations to explain complex topics that Carlos and Adrianna must learn to take the next step along the journey. Users even have a fieldbook that saves the notes they take as they tag along.

“We are consciously trying to instill the fact that science isn’t complete,” Pugliese says. “In the script, we even say, ‘Scientists don’t know that yet.’” Thus, the pink iguana makes the perfect mascot. Much remains unknown about this reptile, which lives only on one side of one volcano in the Galapagos archipelago.

All of these grand ideas went to Brighenti for coding. To make the program fit onto a SolarSPELL, he decided to shift to a web-based platform. “I figured out how to take things from the storyboard and convert them into HTML,” Brighenti says. “I was able to learn as I was building.” The team finished summer number two with a fully functional prototype of one module.

With this one prototype module complete, the project will continue this summer. Research, learn, test, pivot, and work collaboratively for as long as it takes. That’s how you do science. It also helps to be open to new possibilities. “Virtual Galapagos is not like a normal research project where I know where I want to go with it, the students join in, and then there’s bobbing and weaving,” Harpp says. “We wanted to see if we could get any piece of this working at all, because it is from scratch. This one — we’re all in it together.”

— Mark Walden

The Untold History of the Garden State

The stories of African Americans in New Jersey weren’t being written. Graham Hodges decided to change that.

Starting as a slave society in the 17th century, New Jersey is now home to the fifth largest black population in the country. It is also one of the five most racially segregated states in the nation.

Throughout its history, the state has been on the tail end of advancements for black people, including being the last state in the North to emancipate slaves. Though black New Jerseyans are free today, many lead impoverished lives with limited access to education, health care, and housing, a direct result of the legacy slavery holds over the state. These are just some of the themes Professor Graham Hodges explores in his new book, Black New Jersey (Rutgers University Press, 2018).

“New Jersey is seen as the northernmost extension of the Mason-Dixon line, as a place where there’s a lot of racism and a lot of Jim Crow behavior,” says Hodges, the George Dorland Langdon Jr. Professor of history and Africana and Latin American studies. “It’s something that colors the black experience up to the present day.”

African Americans have historically been forced to make personal sacrifices to further advancements for their people. In his book, one of the players Hodges uses to make this point is Marion Thompson Wright, a mid-century academic who gave up her family to become the first black woman to earn a PhD in history. She also was the first black historian to receive a doctorate from Columbia University.

Wright established a guidance program at Howard University, where she studied and taught, to help other black people advance. Her dissertation influenced the landmark court case Brown v. Board of Education. “She definitely normalizes the business of being a black female academic,” he says.

But, in addition to noting her accomplishments, Hodges was also struck by the sacrifice of her personal life and eventual suicide.

It was uncommon for a mother to leave her children in the 1940s, and even more uncommon for her to give up parental rights. But in doing so, Wright was able to pave the way for future female black academics.

Professor Graham Hodges was recently awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship for his project “Black Flight from Slavery in the Americas, 1500-1865.”

“It’s difficult for female academics in many institutions to get ahead because family life competes with professional life. It’s one of those sad statistics that oftentimes the most successful female academics are those who never married or who have no children,” Hodges says. “But that’s not always the case.”

Working on his book, with more than 350 years to sort through, Hodges enlisted the help of those he trusted most — his students. Madeline Canning ’18, one several students who assisted with the book, spent part of summer 2015 scouring the New Jersey archives state Supreme Court records. There, she studied pre-Revolutionary War court cases that involved African Americans accused of federal crimes, such as escaping slavery. Later that summer, she moved on to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., looking at pension requests from African American families of soldiers who died in the Civil War.

This was the first of many research grants for Canning, and she says the opportunity to work with Hodges was invaluable. “What fueled my love of history, and what has maintained it for the last several years, was getting to hold these documents that are older than the country we live in,” she says. “I was getting to look at court cases such as Negro Tom v. The King, which was wild, and an experience I never thought I’d have,” she says.

Beginning with Canning’s pre-Revolutionary War research, Hodges writes of black New Jersey history through to the present day. He ends the ongoing history with a message of perseverance.

“New Jersey blacks have faced such foes in the past and did not flinch from direct opposition to racism and injustice,” he says. “History tells us that they will again.”

— Rebecca Docter

New Faculty Chairholders

Endowed academic chairs and professorships provide resources that support the work of faculty members across campus. Colgate’s Board of Trustees approved a new slate of endowed chairholders during its autumn meeting.

“The efforts made by these four faculty members — both as researchers and as educators — demonstrate the best of Colgate and this university’s commitment to academic rigor in all its forms,” Provost and Dean of the College Tracey Hucks ’87, MA’90 says.

Rick Geier (chemistry) takes on the Warren ’43 and Lillian Anderson Chair in chemistry. Geier, an organic chemist who teaches nanotechnology, will hold the title through June of 2029. Thanks to the Andersons, in addition to the chair Geier now holds, new summer research positions for students and funds to purchase a MALDI-ToF mass spectrometer are available. “This instrument is not a common resource at a predominantly undergraduate institution and we are fortunate to have it,” Geier says. In his research, Geier develops novel methods for synthesizing porphyrinic macrocycles. His publications reveal a steady output of scholarship with sustained involvement of students, who appear as coauthors.

Jill Harsin (history) now holds the Thomas A. Bartlett Chair, named in honor of Colgate’s 11th president. “I will use the resources of the chair to further my research,” says Harsin, whose specialties are in European history, the history of France and the French Revolution, and women’s history. She has both published in and served on the editorial board of the premier journal French Historical Studies. Her book The War of the Streets: Honor, Masculinity, and Violence in Republican Paris presents a narrative history of the turbulent July Monarchy, which encompassed two successful revolutions, three Paris insurrections, and seven assassination attempts against the king and his family.

Timothy McCay (biology and environmental studies), now Dunham Beldon Jr. Chair of natural sciences, studies ecology, biostatistics, vertebrate animals, and natural resource conservation. He sees himself as a terrestrial ecologist, with interests in two groups of animals — shrews and earthworms — as well as the buckthorn, an exotic plant. He is also interested in acid rain and the forest-floor ecosystem. McCay has participated in interdisciplinary collaborations that bring together biologists, geologists, geographers, and other scientists. He has published consistently with Colgate students in his projects.

Mary Moran (anthropology and Africana and Latin American studies) will hold the title of Arnold A. Sio Chair in Diversity and Community through June 2020. Since 1982, she has conducted ethnographic field work in Liberia, focusing on a small southeastern region inhabited by the Grebo people. Her most recent research focuses on the larger process of gender transformation in Liberia. Remembering her Colgate job interview in 1984, Moran recalls meeting Arnie Sio. “From the time I came as a new faculty member, Arnie was a wonderful friend and mentor,” she says. “To be recognized with an endowed chair that honors Arnie’s memory gives me a wonderful sense of a circle being completed.”